Ask why.

… and then keep asking. 🙂

“Ask why five times about every matter.” – Taiichi Ohno

How many times have you solved a problem only to have it rear its head again, possibly with only slightly different details?

Isn’t it nice when you solve a problem and it stays solved?

There’s a technique for root cause problem solving called “The 5 Whys”. It, like many Lean tools, is both simple and powerful. Going through the exercise of asking “why?” multiple times about the cause of a problem lets you dive down through its layers to find the true root cause that, when addressed, can solve the problem conclusively the first time.

And if it’s good enough for the Father of the Toyota Production System, I think it’s worth exploring a bit.

“The root cause is the core issue—the highest-level cause—that sets in motion the entire cause-and-effect reaction that ultimately leads to the problem(s).” – American Society for Quality

The practice when presented with a problem is to:

- Ask why it happened (or is happening), then write down the most obvious answer.

- Then ask why that thing happened, and write down that answer.

- Continue to ask why until you feel like you’ve reached an appropriate depth of root cause – five times is just a guideline, and you may arrive at your root cause sooner or later than that.

Note that the Five Whys isn’t as effective with more complex problems with more complicated causes – the Lean portfolio has other tools for those situations, such as the Ishikawa (or Fishbone) diagram.

But for many of life’s problems, by yourself or in small groups, this technique is a straightforward and effective problem solving tool.

Here’s an example to help illustrate: You get caught speeding.

Asking yourself why you were caught speeding, your answer is because you were late for work. So you write that down underneath:

| Got caught speeding. | Why? |

| Late for work. |

You ask why you were late for work, and then add that answer below:

| Got caught speeding. | Why? |

| Late for work. | Why? |

| Woke up late. |

… and so on, until you feel you’ve reached the root cause:

| Got caught speeding. | Why? |

| Late for work. | Why? |

| Woke up late. | Why? |

| Alarm clock didn’t work. | Why? |

| Batteries stopped working. | Why? |

| Forgot to replace the batteries. |

Now you know, and can solve, the real problem and not just a surface symptom.

Looking at it from a slightly different perspective:

So what if we did what we often do, and stop at the first level of why? Maybe we’d try getting to bed earlier at night as a possible solution… but would that solve the problem? Do you think it might happen again?

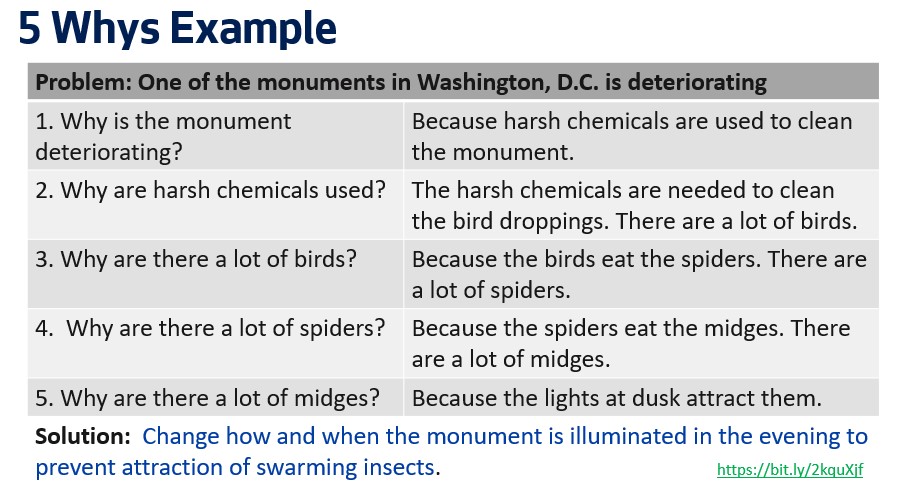

Here’s another frequently cited example problem: One of the monuments in Washington, D.C. is deteriorating.

What if we never went beyond step 1? We might change the chemical being used to one less harsh and see what happens… what do you think might happen, knowing the causes all the way down?

Here’s our card:

When you really ask why, you help to frame the problem properly and truly identify it. You can’t really solve it until you do.

Framing a problem properly helps solve its root cause

Here’s an example of how framing can help. Let’s return to Dr. Jody McVittie’s example, but from a different perspective.

A child wants a toy that another child has. They initially see their problem as “I want that toy” and might solve it by taking it. When they do, because after all it’s the logical solution, the other child protests, and conflict ensues.

What’s the root cause of the conflict? Is it that the first child wanted the toy? Why did they want the toy? Because the other child had it. Why did the other child have it? Because that child wanted it too.

Root cause is simple here. But when the problem becomes “both children want the toy“, many different solution options present themselves. What if they took turns? What if no one had it? What if they played with it together?

… and once again, we have calm. 🙂

Final thoughts

Channel your inner Taiichi Ohno and ask why five times the next time there’s a problem you need to solve.

What do you think about this technique? Does it seem simple enough to try with your child, or even your partner?

Modeling problem-solving with our kids is an engaging way to teach them how to solve their own problems.

Would you consider trying it on a work problem? Have you had any experience with this technique?

Let us know how it goes, we’re genuinely interested!

Discover more from sharing perspectives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks