An experimental post

So the blog is called “Sharing Perspectives”, and there’s a reason.

I propose that the most urgent and vital thing we can learn as sentient beings is to think and feel from another’s perspective.

Perspective is an interesting word to me, full of meaning and implications and possibilities, but the point I’d like to make is that, with enough practice, we can truly imagine ourselves in someone else’s place, either mentally or emotionally, which allows us to cross a crucial gap from sympathy (or even apathy) to empathy.

How is empathy different?

“Empathy is our ability to understand how someone feels while sympathy is our relief in not having the same problems.”

That comes from a group called Psychiatric Medical Care, who explore the differences in more depth in an article posted here. But what I’d like to focus on is the idea that sympathy causes separation, while empathy fosters connection.

From the article:

Brene Brown describes sympathy as a way to stay out of touch with our own emotions and make our connections transactional. Sympathy puts the person struggling in a place of judgment more than understanding. A person seeks to make sense of a situation or look at it from their own perspective.

Further:

Empathy is defined as “the feeling that you understand and share another person’s experiences and emotions” or “the ability to share someone else’s feelings.” It is looking at things from another person’s perspective and attempting to understand why they feel the way they do.

Seeing from another’s perspective makes us more empathetic – not just towards one person, but just a little towards people in general – which fosters connection and understanding.

How can this help?

So what to do with this knowledge? How can we learn to see from another’s perspective? How can we teach our children to?

While some people naturally possess empathy, it’s also something you can learn, develop, and even teach.

To quote one of my mentors:

“The life skill of being able to look at things from more than just your point of view can be taught by simple modeling and observations.” – Dr. Jody McVittie

She uses the example of a child wanting a toy that another child has. The first child unconsciously frames their problem as “I want that toy.” The obvious solution to which, of course, is to take it.

Saying to the child “It looks like you both want that toy” challenges them to re-frame their problem as “we both want that toy”… and suddenly other potential solutions present themselves.

Watch their face as understanding dawns… they want the toy, the other child also wants the toy, and the wheels turn to generate a solution to the newly framed problem.

What if they took turns? What if they played with the toy together?

What if, instead of feeling a need to take another child’s toy away, the first child decided on their own that their solution would be to share?

What would they learn from the situation? And what did they just practice?

Can you imagine if everyone in the world could easily adopt any and every other person’s perspective?

Could there still be violence and hunger, destitution and excess? Wouldn’t this empathy and connection and compassion and understanding foster horizontal relationships between everyone rather than hierarchies and classes?

If we scale down our ambitions just a bit – only for now – we can practice seeing and teach seeing from other perspectives as a way to create, strengthen, and deepen our interpersonal relationships – including those we have with our children.

Especially with our children.

… and now for the experimental part!

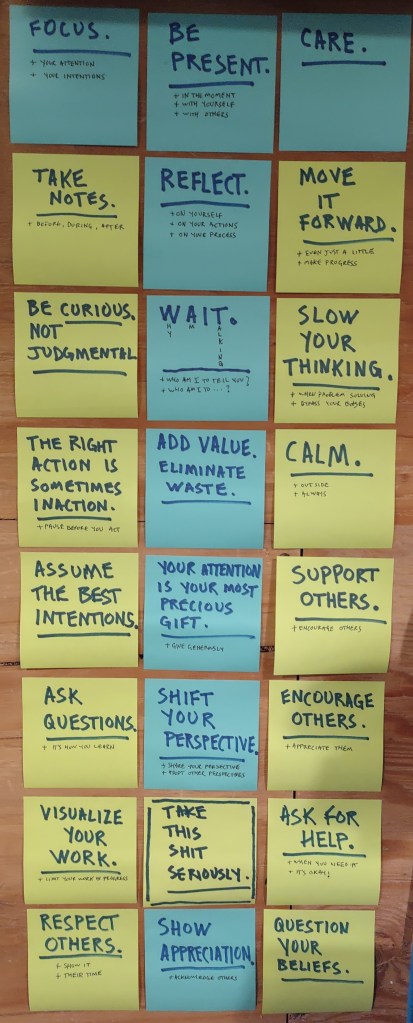

So I have kind of a thing with sticky notes. There’s something interesting to me about the implications inherent in the limited format, the portability, and the physicality as a space to keep track of things.

I’ve been using Personal Kanban, which uses sticky notes to move “things to do” through your own personal value stream, for several years now as a way to visualize my work and life tasks. At some point I started using sticky notes to capture various reminders and thoughts and musings as well, and eventually my house was pretty well pasted with them.

I even started to create artwork using Post-It notes and Sharpie pens. I am deadly serious about that – I participated in an art show at a local gallery in Seattle.

A theme emerges

A theme started to emerge, but I wasn’t sure what it was, or what to call it… some of the notes started feeling more significant than others. Reminders to myself, from myself, of lessons I’ve learned here and there. Ideas reduced to an atomic form. These started to claim their own space on the wall of my home office.

They were inspired in part, I think, by Dr. Rick Hanson‘s work in his book Just One Thing: Developing a Buddha Brain One Simple Practice at a Time, in which he encourages us to explore simple practices, grounded in brain science, positive psychology, and contemplative training, for just a few moments every day.

In the beginning there were maybe 6 or 8 cards.

Currently there are 24.

UPDATE: November 24, 2024 – I’m down to 15 cards, that each have a published article behind them. This is what they look like now:

I still don’t know what to call them… originally I thought of them as goals and thoughts to keep in mind while working. Then I wondered if they were some kind of values list, but that didn’t seem right either. I’m currently thinking of them collectively as “Guidance”, because it occurred to me that all of the best wisdom and advice I could possibly give my son was there – this is no longer a work list, it is a life list.

Shift your perspective.

I’d like to start exploring these thoughts and what’s behind them in a series of posts. Since the title of this post is “Shift your perspective.”, that’s the one we’ll zoom in on a bit.

Each note title may have additional detail below it, usually extensions to or clarifications of the title. In this case, the detail level includes:

- Adopt others

- Share yours

“Adopt others” is fairly well covered above, so let’s finish with a quick look at “Share yours“.

As it turns out the inverse of the above is also true – not only can you strengthen your connections by adopting other perspectives, you can help others strengthen their connections with you by sharing your own perspective.

Sharing your perspective allows others to have a better understanding of where you’re coming from and takes some of the mystery out of interpersonal relationships – and hopefully will encourage others to do the same in return.

What’s your perspective?

Contact us

Please share anything that comes to mind, whether it’s feedback on the website or its layout, suggestions about the content, or anything at all that comes from your perspective and we will get back to you as soon as we can.

Any messages are considered confidential (the message is sent to tim@sharingperspectives.com) and will not be shared under any circumstances.

Arguably the simplest meditation:

- Breathe in, and know that you are breathing in.

- Breathe out, and know that you are breathing out.

… in whatever way feels natural to you.

Deeper breaths can help soothe anxiety. Simply noticing your normal breathing can help ground you in the moment.

Two more quick tips if you have a little bit more than a moment:

- Try simply taking 5 deep breaths. Deep breathing can stimulate the vagus nerve and activate the sympathetic nervous system.

- Take several breaths in a 1:2 ratio – 4 seconds in through the nose, 8 seconds out through the mouth. Feel free to make a whooshing noise as you exhale.

Whatever you’re doing, whoever and whatever is important to you, when the world is on fire and the universe is catching, you still need to breathe.

“For some of our most important beliefs, we have no evidence at all, except that people we love and trust hold these beliefs.

Considering how little we know, the confidence we have in our beliefs is preposterous – and it is also essential.” – Daniel Kahneman

My wife and I argue all the time about actors and actresses in movies or shows that we watch. She’ll point someone out and say something like, “Oh, that’s the same guy that was in the other show we watch”, and I almost invariably react with “No it’s not”, even though she is almost as invariably correct.

But not every time. Sometimes I surprise her, and we look up the person on the interwebs and it really wasn’t the person she thought it was.

And either way, it doesn’t stop either of us from believing that we are right in every fiber of our beings the next time we’re watching a movie.

Are you certain you’re right? Are you firm in your beliefs?

You have the most reason to question them.

It isn’t possible that everything we believe is true. We often think we have all the facts we need to make up our mind, but do we? How did we come by those facts? How did we come by the beliefs they support or reinforce?

When we think we know something, we tend to close ourselves off to new evidence that challenges that belief, and readily accept any new evidence in support of that belief.

We need, from time to time, to reflect on our beliefs and actively question them if we want to ensure they are guiding us in the direction we want to be going. Especially because so many of our beliefs are so deeply tied to our identity and our sense of self.

I’ve been thinking about beliefs and came across an article in Psychology Today that explored many of the ideas I’m interested in examining. I’d like to take this post to break it down in a little more detail.

But there’s more! I also want to get into critical thinking, what it is, and how it can be applied to challenge and in some cases change our beliefs. This comes courtesy of a Medium article by Shari Keller that you may or may not have access to.

What actually is a belief?

In an article for Psychology Today titled “What Actually Is a Belief? And Why Is It So Hard to Change?“, Dr. Ralph Lewis writes:

“Beliefs are our brain’s way of making sense of and navigating our complex world.

They are mental representations of the ways our brains expect things in our environment to behave, and how things should be related to each other—the patterns our brain expects the world to conform to.

Beliefs are templates for efficient learning and are often essential for survival.”

We experience the external world entirely through our senses. Our perceptions and experiences are what ultimately define our beliefs. It is exceedingly difficult to accept that those perceptions and experiences are not necessarily reliably representative of objective reality.

Experience is defined as “practical contact with and observation of facts or events”. But because our experience is subjective, we need information from other perspectives in order to see a fuller and more objective truth.

And it can be hard to recognize this fact – we give so much more weight to what we “see with our own eyes” than we do to the very same subjective experiences of others. But what makes a single point of reference more valuable than multiple points, really?

Because it is uniquely your own.

And because it is uniquely your own you will defend it against all comers. And rightfully so – your perspective is hard won.

“We will more readily explain away evidence that contradicts our cherished belief by expanding and elaborating that belief with additional layers of distorted explanation, rather than abandoning it or fundamentally restructuring it.”

Homeostasis and System 1

Let’s look to Brittanica for a definition of homeostasis:

Homeostasis is any self-regulating process by which an organism tends to maintain stability while adjusting to conditions that are best for its survival. If homeostasis is successful, life continues; if it’s unsuccessful, it results in a disaster or death of the organism.

Homeostasis – a mechanism for early and fundamental life, seems to apply to higher functions as well. So imagine beliefs that we incorporate as part of our core selves, and the tendency to maintain those beliefs and therefore one’s sense of self in favor of the energy expenditure required to question them.

Here I’ll take a moment to touch on Daniel Kahneman’s model of behavior described in his book, “Thinking, Fast and Slow”.

Kahneman posits envisioning our minds as operating as a pair of distinct systems.

System 1 is fast. Very fast. And instinctive. That often has its advantages.

System 2 is slow. It costs more energy, but delivers deeper, more logical results.

System 1 is kind of the default pilot as we go about our day, and whenever we put our thinking caps on, we can access System 2.

System 1 represents a kind of mental homeostasis, where the goal is to keep things in balance and respond quickly and effortlessly to the majority of what life throws at us, ensuring that the system can tolerate minor variation.

System 1 applies our beliefs constantly throughout the day, often with out a single peep out of System 2. If we want to question our beliefs, we need System 2 to do it.

Science vs. faith

So far I’ve talked a lot about science, but not at all about faith. Let’s begin this section with a couple of definitions.

Faith is defined as “complete trust or confidence in someone or something” according to Oxford, while science can be defined as “the systematic study of the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world through observation, experimentation, and the testing of theories against the evidence obtained.”

Another way to compare and contrast the two is simply:

“Faith is based on belief without evidence, whereas science is based on evidence without belief.”

Dr. Ralph Lewis, in Psychology Today, tells us more:

“Science values the changing of minds through disproving previously held beliefs and challenging received authority with new evidence. Faith is far more natural and intuitive to the human brain than is science. Science requires training. It is a disciplined method that tries to systematically overcome or bypass our intuitions and cognitive biases and follow the evidence regardless of our prior beliefs, expectations, preferences or personal investment.”

This makes science sound hard. And it is, of course. If it wasn’t, everyone would be doing it. All the time. At least, that’s my belief. 🙂

All of this suggests that beliefs are highly resistant to change, and while that is often for good reason, in many cases, when we examine them, they really aren’t based on anything we would consider to be solid evidence if it belonged to someone else.

How can we safely question our beliefs?

So it’s hard to question our beliefs, but I think it’s necessary. How can we do this without threatening our very identities?

The first takeaway is to recognize. Understand the experiences and biases that make up your System 1 belief structure. This provides an opportunity to bypass your biases when forming and considering beliefs.

Second is that potentially self-concept-altering challenges to beliefs are effortful and exhausting. In order to be open to questioning our beliefs, all else must feel stable. And we need to slow our thinking in order to accommodate the effort that our System 2 will require.

Encountering a belief, ask yourself from time to time, “Is it really true?” Genuinely question things you believe, and be truly open to new evidence that might change the way you think about something.

If it’s a big belief, it’s a lot to question all at once, so allow a more comfortable conversation with yourself by opening to something smaller. For example, if the death penalty is an issue where you have strongly held beliefs, test them by starting with something like whether a particular execution method is more or less humane than another.

And our beliefs don’t need to change all at once… it can start with an opening to a possibility, and then using critical thinking skills to develop your own questions to form your own arguments for or against a belief, and draw your conclusions from there.

Critical thinking

Critical thinking is the ability to analyze, evaluate, and interpret information to make a judgment or decision. It helps us make sure that we have good reasons to support our beliefs.

Critical thinking teaches what is and what is not a good argument supporting a belief. It teaches what is a good reason for believing something – one that provides a high probability that something is true – and what is a bad reason for believing something.

For a fuller picture, watch the 10-minute video above.

But here are some characteristics of critical thinking:

Questioning: Critical thinkers question what they read, hear, say, or write. They also acknowledge and test assumptions they’ve previously held.

Making connections: Critical thinkers connect logical ideas to see the bigger picture.

Making informed decisions: Critical thinkers make decisions based on reliable information.

Being objective: Critical thinkers identify and solve problems in an objective and systematic way.

Communicating ideas: Critical thinkers can advocate their ideas and opinions in a logical way.

Especially in an emotional moment, this kind of introspection isn’t necessarily easy – emotion is fast and logic is slow. So of course it’s challenging to apply critical thinking in the moment.

But you can always reflect on the moment afterward. In fact, reflective thinking is another term for critical thinking.

From the Medium article linked above, as a parent you can even help to teach your child critical thinking by:

- using open-ended questions

- encouraging innate curiosity

- using project based learning and experiential learning

- using discussions and debates that encourage them to see things from a different point of view.

From Shari Keller:

“When we teach our kids to question, analyze, and understand the world around them, we’re setting them up to handle challenges — with curiosity and confidence, and with humility and deep reflection.”

Skepticism

At some point the word “skeptical” became interchangeable with “cynical”, and it developed a negative connotation.

But being skeptical is a good thing! We need to be skeptical to protect ourselves from being fooled.

The chart below was inspired by Melanie Trecek-King at Thinking Is Power in her article “How Skepticism Can Protect You From Being Fooled” – please click through and read it if you have a few minutes and would like to go a little deeper on the subject.

A skeptical person is happy to believe something, provided you give them reliable evidence. Their level of belief is entirely dependent on the available evidence.

Skepticism is a central requirement of both good journalism and good science.

Summary

Our beliefs are often strong, and changing them is often hard. Sometimes with good reason – imagine if you had to consciously believe that you needed to breathe and think about it constantly to avoid suffocation.

But just because something is hard doesn’t mean it isn’t worth doing, and with time, and skill, and practice, we can learn to challenge even our most closely held beliefs, and only form new ones with sufficient evidence.

Lately I try really hard to not react in immediate disagreement when my wife thinks she’s spotted someone in a movie without taking a long, hard look and a think about it.

What I’ve really learned is not to challenge her – she has a much higher probability of being right than I do when our beliefs conflict.

But when I’m confident I have enough evidence to support my claim, I’m not afraid to be right either. 🙂

Here’s our card:

How have you been able to question your beliefs?

What closely held belief will you challenge today?

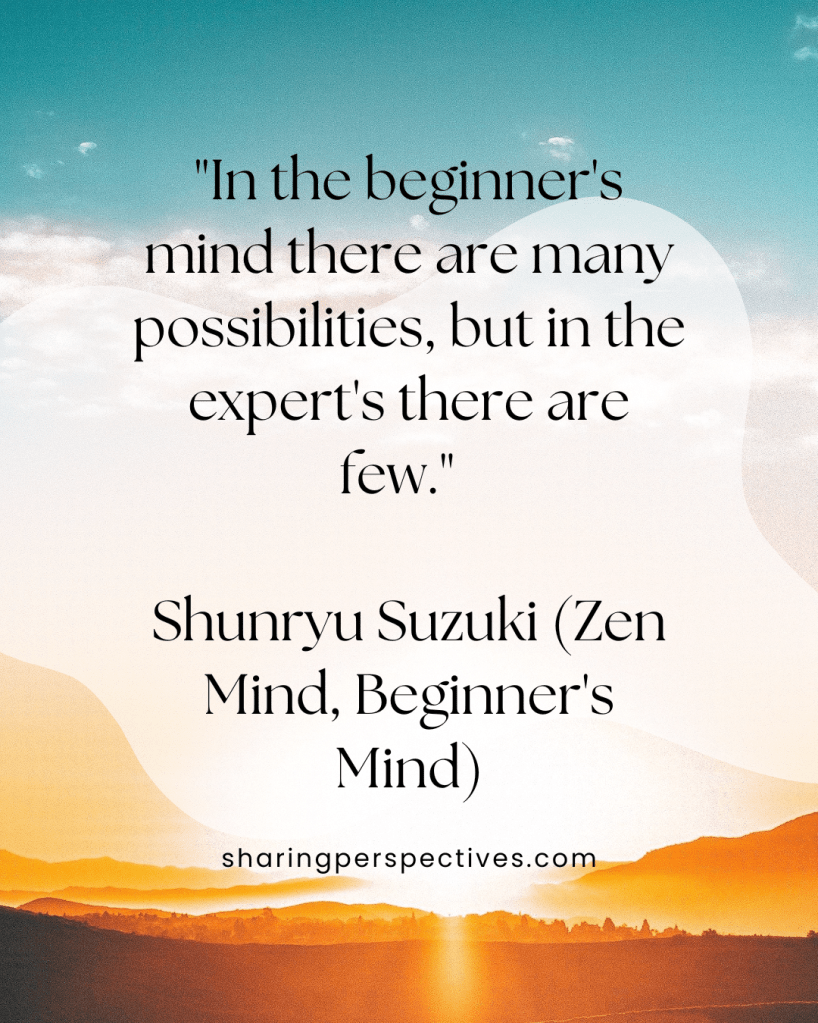

“In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.” – Shunryu Suzuki (Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind)

My wife’s birthday, which she shares with a close friend, is coming up, and she mentioned a specific cake, made by a bakery in Austin, Texas (we live in Seattle, Washington). She opined that it would be lovely to have such a cake to celebrate the pair of birthdays, and wondered if they might ship such a thing out of state.

Now, in my uninformed opinion, it seems impractical to expect to be able to ship cross-country something as delicate as a birthday cake. And despite a lack of direct knowledge in these matters, I felt reasonably confident in expressing that opinion.

Surprisingly, this was called out as unsupportive.

Looking back now, I wonder if instead of passing judgment on my wife’s pondering, I might have instead developed a sense of curiosity about how she might imagine such a thing could be feasible. Or better yet, resolved to answer the question definitively by searching for the bakery’s contact information.

It’s a question I’ll try to ask myself more often, in my never-ending quest to basically be less of an ass.

But more than that, I want to encourage adoption of a kind of curiosity-based approach to life in general that includes and expands on teachings from different domains.

Mindful curiosity

In Zen Buddhism, the term “beginner’s mind” refers to a mindset that is free from preconceived notions and judgments. Rather, it represents a state of pure curiosity and receptivity.

You can also think of beginner’s mind as “don’t know” mind.

When we’re new to something, we don’t know anything, and anything is possible. As an expert we gain knowledge and proficiency, but as more is known the doors start to close on possibilities.

When we’re beginners we don’t even know what we don’t know, and adopting this mindset even at times we think we know something can create a wealth of opportunities to learn and grow further.

That isn’t meant to imply that expertise is bad… just that sometimes, when you suspend that expertise for a moment, you might open yourself to a novel approach to a problem.

Imagine the approach that a small child takes to pretty much everything in their environment when given free reign to explore. Imagine approaching everything and everyone with that same state of expectant curiosity and wonder.

It’s a mindset that mindfulness practitioners the world over seek to adopt. The concept itself is simple enough. But life can be complicated, so its practice can be challenging.

The practice of the half-smile

The practice of the half-smile, from Yvonne Rand, a Soto Zen Buddhist priest and meditation teacher, can help cultivate beginner’s mind:

“The practice of the half-smile has nothing to do with feeling like smiling. For those of you who have not done this practice before, you can think of it as “mouth yoga.”

– Yvonne Rand

Just lift the corners of your mouth slightly—not a full smile or a grin—for the space of three full breaths.

Let your attention be on the sensation of slightly lifted corners of the mouth and then with the three breaths.”

Don’t rush the breaths… experience them fully. Don’t change the breath… observe it as it is.

For those with a meditation practice, the half-smile is an easy way to return to what you might think of as your “Buddha space”. 🙂

You can practice it as the first thing when you wake up in the morning, while standing in line, every time you get into or out of your car, any time when you have, or want to create, a moment to open yourself to the possibilities that life will present you with.

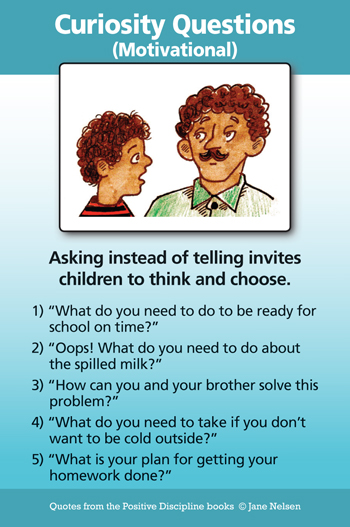

Curiosity questions

In Positive Discipline we learn to ask younger children questions instead of telling them what to do. These are known as curiosity questions.

The questions above are alternatives to statements or commands like: “Come on, it’s time to go, we’re late!” Or, “I’ve told you five times to do your homework! If you don’t get it done you can’t go to your friend’s house.”

The idea is that by being curious instead of judgmental, we allow space for information we didn’t previously have available, and we allow the child to determine how they will achieve a goal, which gives them agency. It also helps children explore the consequences of their choices, rather than imposing consequences upon them. They feel respectfully included instead of blamed or shamed.

From Jane Nelson in a Positive Discipline blog post about curiosity questions:

“When children hear a command, a signal is sent to the brain that invites resistance. When children hear a respectful question, a signal is sent to the brain to search for an answer. In the process they feel capable and are more likely to cooperate.”

Think for a moment about how you feel when you’re given a command. I myself have some kind of instinctive internal rejection of authority that kicks in when someone tries to issue me a command. I don’t like it. And I’m more than likely to want to do the opposite.

And to kick your game up a notch, you can practice using conversational curiosity questions specifically:

“Conversational curiosity questions take more time than motivational curiosity questions because you are doing more than inviting the child to think of a solution to a simple task that requires attention, such as, “What do you need to do to get your work done on time?” Conversational curiosity questions require just what the name suggests: a conversation.”

Asking questions with genuine curiosity can change almost any atmosphere from negative to positive.

And pretty much any problem can be turned into a question. If you want to let children know they’re being too noisy, you might ask something like “Who thinks it’s too loud in here? Who thinks it’s too quiet?” for example.

When faced with a parenting challenge, even a difficult one, we can layer curiosity questions in a measured approach to resolving it.

- “What happened?”

- “How do you feel about it?”

- “How do you think others feel?”

- “What ideas do you have to solve this problem?”

Notice that the first question is fact-based, the second and third are “heart” based, and the last is “head” based. This allows for feelings and emotions to be acknowledged and understood before attempting to solve a problem.

And again in Jane’s words:

“The end result is focusing on solutions to the problem instead of focusing on consequences.”

This practice teaches children so much at once. They have an opportunity to develop their language for emotions, they learn empathy, they learn problem-solving skills, and when it all comes together it’s a beautiful thing.

But the benefit of using curiosity questions goes far beyond the domain of parenting. For example, I’ve found that using curiosity questions with my team at work is a thousand times more effective than issuing directions or orders (micromanagers of the world, please heed). And when I’m in a dispute with a service provider I ask curiosity questions to help me better understand their perspective.

In fact, if you replace the words “child” and “children” above with “spouse”, “colleague”, etc., you might find that curiosity questions are a wonderful practice to use with people in general.

Final thoughts

Here’s our card:

To teach ourselves to be curious rather than judgmental, we can practice adopting beginner’s mind and learn the language of curiosity questions.

But I’d like to close with a call to action to try to be more curious in general. Learning is a lifelong occupation, and if you direct that learning where your curiosity goes, you’ll be all the more excited about what you learn, and all the more able to put it into action. So be curious, and then free that curiosity to wander the world and come back with whatever it leads you to.

Do you have any thoughts about mindfulness or beginner’s mind? Have you tried to use curiosity questions, as a parent, or in life in general? Please share your perspective in the comments!

“Awake at night, I cannot sleep,

I long for but a taste

Of silent shadows wrapping ’round

In Quiet’s calm embrace.An island bright in waters cold,

A city in the sky,

I long for peace I cannot grasp

Though all around it lies.”

I have had battles with sleep for as long as I can remember. Doctors would ask if I had the most trouble falling asleep, or staying asleep… and my answer, invariably, was “Yes.”

And yes, that was part of the problem – I saw my efforts to get a reasonable amount of sleep as a battle for a very long time.

I have sleep apnea, and I can’t tolerate any of the various machines designed to treat that malady. And it’s severe… if I remember correctly I stop breathing something like 30-40 times an hour while I sleep.

I also have this weird thing where ear worms – little bits of catchy music – get stuck in my head, and the little bits turn into big bits, and suddenly there’s a whole song playing in my head. It seems innocuous enough – I mean, everyone gets these from time to time, right? – but I promise you it is maddening.

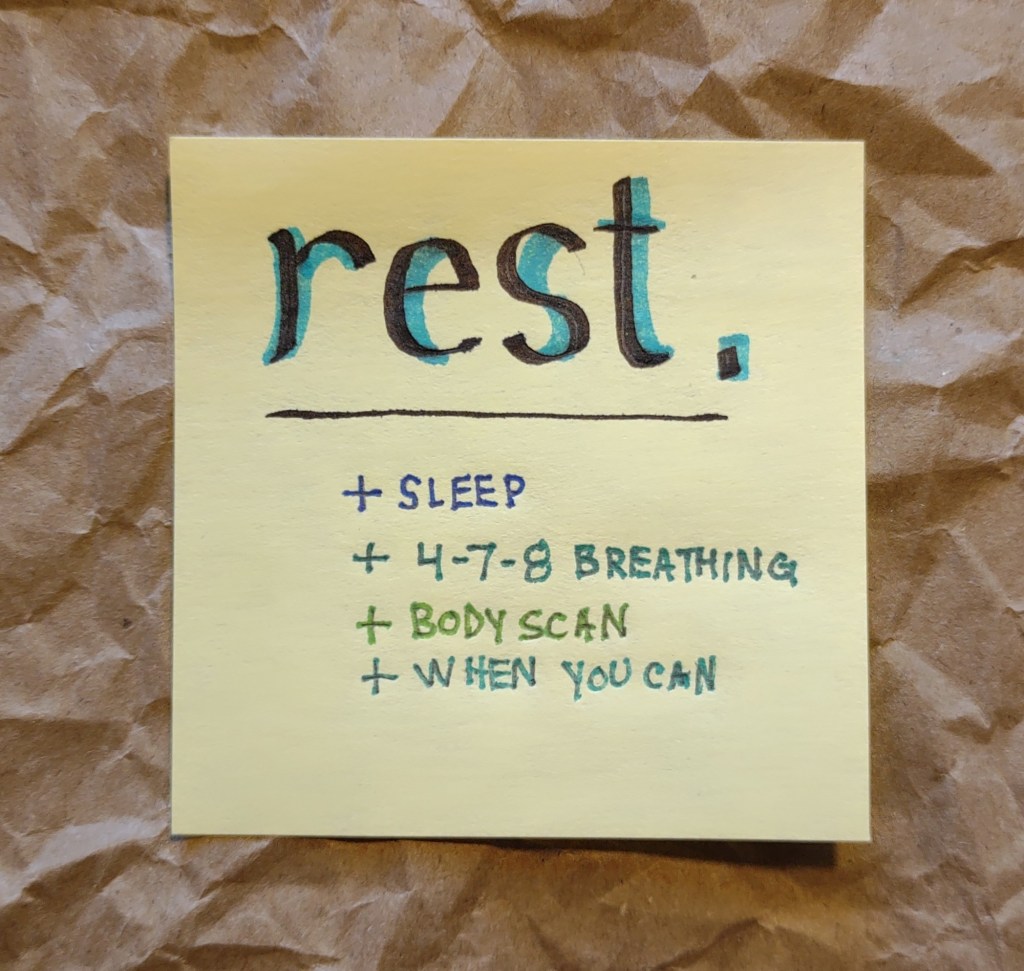

After much struggle I decided to stop struggling. I’ve done what I can do to make my sleeping environment as conducive to rest as possible, and I can’t do any more. So I accept that I don’t sleep as much or as soundly as many other people, and then I make sure that I get rest when I can, and make it a priority when I need it.

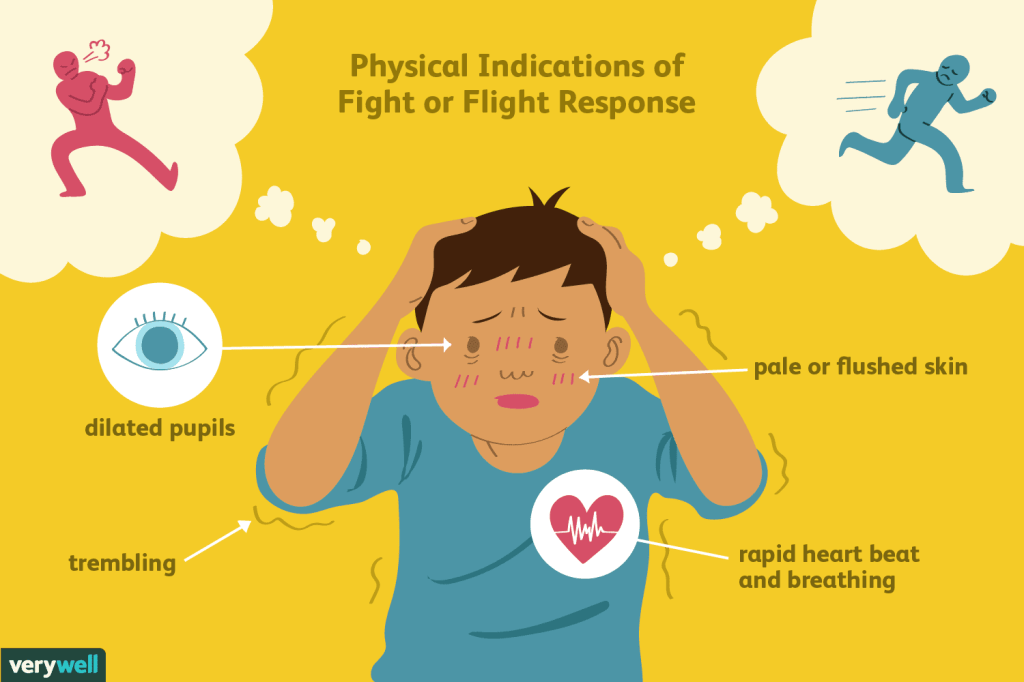

It’s important for self-care to rest when we need to. You can’t save your family or the world when you’re running on fumes. Especially during times of high stress when your “Fight or Flight” reaction is triggered almost continuously.

Sleep

First and foremost, if you aren’t getting enough sleep – please STOP and fix that. 🙂

Do what you need to do – buy a new mattress, put blackout shades on your windows, practice better sleep hygiene, see a sleep doctor, whatever it takes for you to get enough rest.

Study after study shows the impact of not enough sleep on the human mind and body. A recent Wired article delves into how the brain decides what to remember.

“New studies … have suggested that the brain tags experiences worth remembering by repeatedly sending out sudden and powerful high-frequency brain waves.

Known as “sharp wave ripples,” these waves, kicked up by the firing of many thousands of neurons within milliseconds of one another, are “like a fireworks show in the brain,” said Wannan Yang, a doctoral student in Buzsáki’s lab who led the new work, which was published in Science in March.

They fire when the mammalian brain is at rest, whether during a break between tasks or during sleep.”

You can’t be awake all the time or asleep all the time for obvious reasons. But maintaining the balance between periods of waking and rest will keep the brain optimized for retaining information.

And when the mind rests, or is left to wander where it will, remember that those fireworks are going off. You want those sharp wave ripples!

Fight or Flight

If you’ve ever been alone in the house, or even with others there, and heard a strange noise that put your senses into overdrive, paused your breathing, and caused your heart to race, you’ve experienced Fight or Flight, when the brain tells the body it’s under threat and better get ready to choose.

This instinct was critical to our ancestors that needed to be alerted to things like tigers in the brush, but evolution hasn’t had a chance yet to catch up to modern life.

So we find Fight or Flight being triggered by things like an email from your supervisor or an unexpected call from an ex – stressful situations where the continued existence of the self is not truly under threat, but the brain still releases all the chemicals and instructions it would release when our lives are truly in danger.

Fight or Flight is a physical stress response, and it can be met with a physical response.

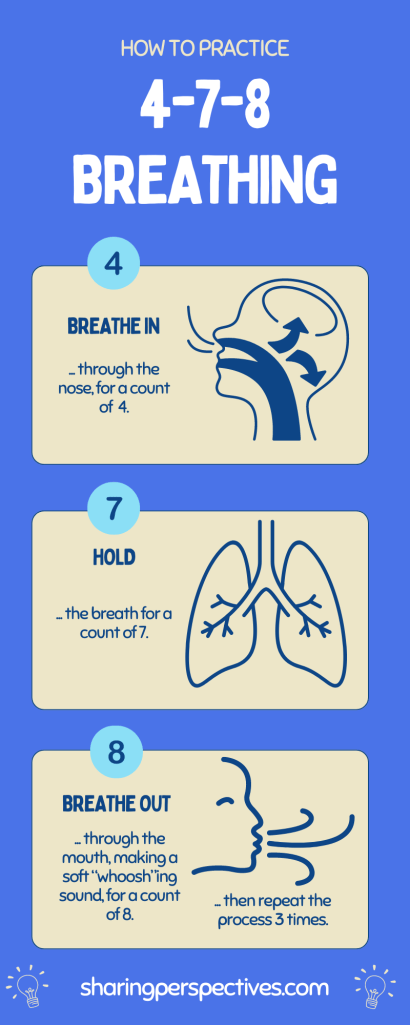

4-7-8 breathing technique

From the 16personalities article Breathing to Reduce Stress: The 4–7–8 Method, two of the most noticeable – and easily adjusted – physical reactions to stress are:

- Shortness of breath

- Shallow breathing

When we find ourselves feeling particularly stressed out, one intervention that can help us decrease stress and become more relaxed is the 4–7–8 breathing method. This technique is very easy to do pretty much anywhere, and it’s a wonderful tool for when stress levels are especially high.

The four simple steps are as follows:

- Breathe in through the nose for a count of 4.

- Hold the breath for a count of 7.

- Exhale through the mouth, making a soft “whooshing” sound, for a count of 8.

- Repeat this process three times.

And if you like, take the opportunity to loosen up your body and work out any kinks – roll your shoulders, stretch your arms to the sky, shake out your limbs.

This isn’t a comprehensive solution to completely ridding ourselves of stress, but it does allow us to relax, regain control of our physical bodies, and release some of the stress we’ve been feeling.

“Sometimes something as simple as breathing calmly is enough to bring a sense of peace during a particularly stressful moment.”

Body scan

Another way to help relax is to perform a mindfulness meditation called a body scan.

According to Headspace:

“While there are many specific meditation techniques that can be used to help us find stability of mind and cultivate mindfulness over time, one of the most accessible practices is a body scan meditation, during which you bring attention to your body, noticing different sensations, as you mentally scan down, from head to toe.

Here is one set of instructions for how to do this:

- Find a place to lie or sit comfortably, ideally free from distractions.

- Close your eyes and bring your attention to your breath.

- Notice the sensation of air rushing in past your nostrils, and rushing out again.

- Notice the sensation of your chest or belly rising and falling.

- Bring your attention to your feet.

- Notice that you have a sense of them and know where they are without moving them.

- Consciously relax the muscles in your feet.

- Let yourself feel a soft, warm glow enveloping them.

- Let your attention flow up from your feet to your lower legs.

- Consciously relax your legs as well.

- Continue up through your body until you finish with your head and face, noticing any sensations you encounter along your journey.

- Imagine the soft warm glow enveloping your whole body.

- Bask in that glow for a moment, then open your eyes and take another moment to re-orient yourself.

If you’d like to try listening to a quick 3-minute guided body scan meditation, Headspace has one here.

You don’t need to lie down if you don’t want to, you can do a body scan while sitting comfortably in a chair or on the couch.

I’ve actually used a guided body scan meditation in the Calm app as a tool to help me sleep. I usually feel so incredibly and completely relaxed at the end, and it’s easier to drift off into slumber from that point.

Rest throughout the day

Since I don’t sleep as much as most people do at night, I make it a point to pay close attention to what my body is telling me during the day, so that I can be sure to give it some rest when I need to.

- Build in breaks throughout your day – could those hour-long meetings really be 55 or even 50 minutes? Allow yourself and others time to rest and reset between engagements, and everyone will be in a much better position to bring their best selves.

- Or maybe you work at home – could you make it a point to pause every now and then and maybe go outside for a short walk, or even just to stand in nature and be present with it?

- Don’t take on too much at once – this may seem obvious, but in my efforts to accommodate everyone I often don’t give any real thought to my own available bandwidth before agreeing to a task. I remind myself that, after careful consideration, it’s okay to say no sometimes.

- Limit your work in progress – more specifically, if you use a visual task management system like a kanban board (or really, even if you don’t), you can apply the practice of limiting your work in progress. Our brains can only handle so many things at a time, so taking on too many of the “things” is a sure path to burnout or breakdown of the system.

- And that’s you. You’re the system. 🙂

Final thoughts

When it comes to self-care, I keep thinking about the instructions we hear from flight attendants to put on your own oxygen mask before helping someone else with theirs, and I think that we aren’t able to bring our best selves into our interactions in the world if we don’t make it a priority to take care of ourselves first.

Seriously… we all need to sleep.

When you’re going about your day and find yourself under stress, try the 4-7-8 breathing technique to help you relax and calm yourself.

When you have time, and if you’re so inclined, practicing mindfulness and particularly body scan meditations can help build awareness and resilience, and help provide you with a few minutes of unadulterated rest. Who knows, maybe it will even help you sleep!

And if all else fails, please listen to your body and your mind, and find a way to rest, your way, when you can. It doesn’t matter how, it doesn’t matter where, if you’re out of gas and you know it, take 5. What’s the worst that could happen if you do?

Now, please, for all our sakes… go get some rest. 🙂

And let us know how you get rest in the comments!

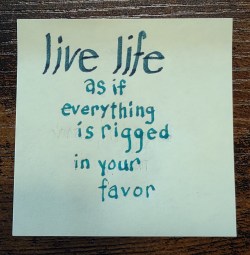

… as if everything is rigged in your favor.

The great poet Rumi wrote this in the 13th century. That’s the 1200s. So, a long time ago, is all I’m saying.

Of course, he didn’t write it in English.

He wrote mostly in Persian, but occasionally in other relatively local languages as well.

I’m not sure what the original word or phrase was that translates to “rigged”, but regardless of the details, I think the power of the quote remains.

“Live life as if everything is rigged in your favor.”

I’d like to invite you to sit with these words for a moment and think about what they might mean to you.

For me, it’s a mindset that helps me remember that there are no evil forces conspiring to hold me back.

It’s a reminder that I can choose to adopt a different mindset – that we have every opportunity, and even a responsibility, to be open to accept whatever life is presenting us with at the moment.

In a spirit not merely of non-judgment, but if we can manage it, one of positivity.

Because even in a “bad” moment, there is something to learn… isn’t there?

Isn’t there an opportunity to be, and to present, our best selves, even in that moment?

Is it possible that even difficulty and suffering can lead to resilience and wisdom?

So as long as we’re spinning conspiracy theories in our minds, why not assume that the universe wants us to succeed, rather than fail? 😊

I know that when I try to live my life this way, it feels like opportunity after opportunity opens up before me. I feel empowered, and powerful. And in control. For a change. 🙂

Richard Kronick explores Rumi’s quote more deeply in a contribution to the Huffington Post – hop on over if you’d like to see another perspective.

I’d love for you to share your own perspective in the comments!

The benefit of the doubt is free to give, and a treasure to receive.

Hanlon’s razor is a saying that reads:

“Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.”

In simpler, and kinder, words:

“Some bad things happen not because of people having bad intentions, but because they did not think it through properly.”

The original quotation is attributed to Robert J. Hanlon of Scranton, Pennsylvania, US.

There are many similar sayings.

One example is “Never ascribe to malice that which is adequately explained by incompetence.” Which is perhaps a bit more forgiving.

We can be kinder still by saying “Never ascribe to malice that which is adequately explained by ignorance.” But it’s still focused on the negative, and the word “ignorance” unfortunately has many negative connotations, though it implies to me only a sense of not knowing.

Or… we could flip it around to make it a positive, and say:

“Assume best intent.”

This feels like the kindest way to capture this sentiment. In my mind it essentially means to give someone the benefit of the doubt – at least until they give you an actual reason not to.

Notice that it doesn’t say “positive” intent, as in the graphic at the top. I’m on the fence about that word – it’s true that someone’s intent may not always be positive, but they may be doing the best they can at a given moment.

I was listening to my wife the other day and I was trying my best to listen fully. She made a comment that I felt was critical of me and my behavior when I paraphrased something she had said back to her, when in my mind I was doing my best to be supportive.

But applying this principle of assuming best intent, I stopped for a moment to think about what *exactly* she had said, and how she most likely intended for it to be received, regardless of what thoughts I was having at the time, and I realized that she wasn’t inside my brain and couldn’t possibly know what my own intent was, only what she felt as a result of what I said.

I realized that her intent was most likely not to criticize me, but to offer advice about how best to communicate with her in the future. And if I had given her the benefit of the doubt in the first place, I most likely would not have reacted the way I had.

A more specific example… recently my son needed to get up early so that the whole family could take a Chef’s Tour of Pike Place Market in Seattle that my wife had already bought the tickets for.

I woke him 30 minutes before the time that we needed to leave the house in order to make the scheduled tour, weighing his need for sleep with the time it takes him to get ready.

15 minutes prior to departure, I checked on him again, and he was still in bed. Starting to get frustrated, we worked out that he would get up and get ready on his own without need for additional reminders. I took him at his word, and left.

5 minutes prior to departure… still in bed. Now I was full on frustrated – was he trying to get out of the event with his grandparents? Did he not know how much the tickets were? I told him if he wasn’t able to get up and go with us he would not only owe us the money for the ticket he didn’t use, but we wouldn’t bring him back anything from the market.

Yeah, that didn’t help.

Finally, I thought to ask him why he was having so much trouble getting up to go with us. He has medically-related anxiety issues, so I asked if that was what was going on, and he said yes. And I suddenly realized in that moment that I hadn’t let him know the night before what to expect. And that he was doing the best he could under the circumstances.

Immediately I felt horrible for berating him and essentially threatening him. I apologized for doing so, told him of course we’d bring him something back, announced that he would not be joining us, and gathered up the others for the event.

Looking back, if I had only assumed best intent when he was having trouble getting out of bed to begin with – which was actually atypical lately – I could have saved everyone a lot of time and trouble.

Looking ahead, I’ll try harder to assume best intent, from basically everyone around me. 🙂

Own them. Befriend them. Learn from them.

“Mistakes are the proof that we are human and flawed, but also capable of growth and improvement.” – Brené Brown

“Your mistakes do not define you; they educate, empower, and enable you to reach your true potential.” – John C. Maxwell, Failing Forward (2000)

I made a mistake today.

I zigged when I should have zagged, and things ended up differently than they might have, and I was left to confront the ramifications of my choices.

See, I wanted to write “poor choices” there, but that casual addition has the weight of negative judgment applied to it. I’m trying to practice viewing my mistakes from a perspective of curiosity, but the negative connotations associated with the word “mistake” are deep and broad and, especially in times of stress, present in my thoughts and emotions when I make them.

Does that sound familiar, at all?

When I think back on my mistakes – and I’ve made a few – they come in a couple of different flavors. Some bring up a sense of shame and failure, while others remind me of something I learned from the experience.

The difference doesn’t seem to be in how I view mistakes now – it seems to come from how I viewed the mistake at the time. And how I viewed the mistake at the time depended in part upon how others reacted to the results.

In Positive Discipline (and, interestingly, in Lean manufacturing and management), mistakes (or the resulting problems) are viewed not as something to be avoided but as opportunities to learn. Framing them this way takes the sting out of them, which makes them easier to own, and easier to bring a curiosity to about what might be learned from the experience.

Mistakes are something to be celebrated, because with them come opportunities.

Mistakes in Positive Discipline

In Positive Discipline, we learn to “See mistakes as opportunities for learning.” But “mistakes” come with baggage.

From Jane Nelson in the above article:

“When parents and teachers give children negative messages about mistakes, they usually mean well. They are trying to motivate children to do better for their own good.

They haven’t taken time to think about the long-term results of their methods and how the decisions children make stay with them for the rest of their lives.”

Take a moment to think back about how if felt when you made a mistake as a child – breaking a favorite vase, forgetting to come home on time, neglecting to study for a big test – and what the word means for you now.

“Close your eyes and remember the messages you received from parents and teachers about mistakes when you were a child.

When you made a mistake, did you receive the message that you were stupid, inadequate, bad, a disappointment, a klutz?

When hearing these messages, what did you decide about yourself and about what to do in the future?”

It’s important to remember that “Children can truly learn the courage to be imperfect when they can laugh and learn from mistakes.”

Cast mistakes in a positive light – “Congratulations! You made a mistake! What did you learn from it?” – and begin to take away some of the stigma that’s associated with them.

Positive Discipline teaches the 4 R’s of Recovery from Mistakes:

- Recognize that you made a mistake. Feel the embarrassment, and let it go.

- Take Responsibility for your mistake. Without blame or shame.

- Reconcile by apologizing if others are involved.

- Resolve to focus on finding solutions. Together.

We can take a moment to connect with our children, then walk through these steps with them to help them recognize their mistake and the attendant opportunity.

Mistakes in Lean

Mistakes in the Lean manufacturing and Lean management contexts are “problems“. The word conjures up similar negative associations for many of us, and just as similarly needs to be de-stigmatized.

In our training deck for our Lean 8-Step Problem Solving process in the IT Department at the City of Seattle we open with a discussion of the benefits of continuous improvement as a problem solving approach. The general idea is that many incremental changes add up to huge improvements in processes, and the mindset is one of continuously striving for perfection.

But a shift in mindset is needed in order to make the most of the opportunities presented by problems or mistakes.

For example, in a conventional workplace, we tend to:

- Hide problems

- Rely on leadership for solutions

- Jump to solutions

- Treat symptoms

- Base decisions on anecdotes or assumptions

- Do little follow-up

But in a Continuous Improvement workplace, we learn to:

- Treat problems like opportunities

- Develop problem-solvers

- Slow down thinking

- Analyze root causes

- Base decisions on facts and data

- Build in a plan to study results and make adjustments as needed

Can you see the ways in which a Continuous Improvement workplace sounds a lot like a Positive Discipline family?

We then challenge our trainees to think of a problem as the difference, or “gap“, between what should be happening and what is actually happening.

When we can make this shift in our perspectives, problems become opportunities to close the gap and deliver better products to our customers. Or better relationships with the important people in our lives. 🙂

It’s a major shift from seeing a problem or a mistake as a failure to seeing it as an opportunity. But if we can manage it, and teach it to our kids, so many wonderful things can happen.

Mistakes in innovation

Mistakes are often a key component of innovation. Thomas Edison famously made many mistakes on the path to some of his greatest inventions.

Here are the results of some of the most fortuitous mistakes in innovation:

- Chocolate chip cookies – Ruth Graves Wakefield, co-owner of the Toll House Inn, was hoping the chopped up chocolate chunks she added to her cookies would melt evenly throughout the cookie. Instead, she got chocolate chips!

- Microwave oven – If it wasn’t for a candy bar melting in Percy Spencer’s pocket in 1945, the microwave oven may have never been invented!

- Penicillin – Scientist Alexander Fleming left his lab a mess because he was in a rush to go on vacation.

- Super glue – During World War II, Harry Coover, a chemist for Eastman Kodak, was trying to create a suitable plastic for gun sights…. but he failed!

- Post-It notes! – Spencer Silver, a chemist for 3M, failed in his attempts to make heavy-duty adhesive for the aerospace industry. The best he could do was a lightweight but reusable temporary adhesive.

That’s right… without a mistake, Post-It notes, and therefore most likely this blog, wouldn’t exist.

Final thoughts

Here’s our card:

We make mistakes:

- To learn

- To know

- To own

- To grow

I find that if I try to ask curiosity questions about a mistake immediately after I make it, I’m much more likely to view the mistake in a positive light than in a negative one. And I’m even more likely to learn something from the experience.

And even better – I’m more likely to act to take advantage of the opportunities it offers.

I encourage you to make and own as many mistakes as you can, and to encourage your children and your colleagues to do the same. 🙂

What’s the biggest mistake you are glad to have made? Share with us in the comments!

“He who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead; his eyes are closed.” – Albert Einstein

“Through the sacred art of pausing, we develop the capacity to stop hiding, to stop running away from our experience. We begin to trust in our natural intelligence, in our naturally wise heart, in our capacity to open to whatever arises.” – Tara Brach

When I started this blog, a little over 10 years ago, I was seeking enlightenment. Among other things.

I practiced meditation and yoga. I took karate lessons. I sought out a local Buddhist monastery and explored the work of Tara Brach, Rick Hanson, Thich Nhat Hanh, and other mindfulness advocates and teachers.

Meditation never took as a daily practice for me, but I did learn some key principles that I try to apply in my daily life. One of these principles is the concept of the sacred pause.

Whenever I sense that I’m at some sort of crossroads, when the choices I make will echo into eternity (well, maybe not eternity, but at least for some time), or when I sense myself responding in a way that is not in harmony with my life goals – whether I’m in a meeting at work, working on a project, talking with my wife or my son, collaborating with colleagues, or anything else – I try my best to insert a pause to pay attention and check my intentions.

One area that provides opportunities to practice consistently are my occasional disagreements with my lovely wife. My wife insists that she is unable to pause most of the times she might want to, because… well, hormones. And she has a point – sometimes our emotions or our bodies take us away.

But that doesn’t mean it isn’t important to try to come back. 🙂 So I do my best to pause for us.

What does it mean to pause?

For me, it means to stop, even if just for an instant, to pay attention to my intentions. To take a moment to ground myself in the present moment to focus and reflect, even if only for the tiniest of moments, on my intentions, both in that moment and in the long term.

I know, that’s a lot to pack into a moment, but if you can learn how to do it, it’s a powerful practice. And a really neat trick. 🙂

Why are attention and intention important?

Deepak Chopra describes it this way:

“Attention is focused awareness. Intention is awareness given a purpose.”

In order to open the opportunity for a pause, we first need to be paying attention to what is happening now. Only then can we evaluate the harmoniousness of our next action to further our intentions.

To remind us of our intentions and what is most important, we need to engage our higher thought processes. System 1 is not up to the task… we need to engage System 2.

If you haven’t read “Slow your thinking“, here’s a quick summary of Daniel Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 from The Decision Lab:

“System 1 thinking is a near-instantaneous process; it happens automatically, intuitively, and with little effort. It’s driven by instinct and our experiences. System 2 thinking is slower and requires more effort. It is conscious and logical.”

And of course to get better at this skill, as with any skill, we need to practice.

So let’s break it down.

To learn to pause, we need to:

- Learn how to come back and be present

- Slow our thinking

- … and practice.

It isn’t always convenient to insert a long pause to gather your thoughts, especially in emergent situations. But the longer you practice pausing, the less time it will take. And in those times without the luxury of time we can start with a tiny, little, unassuming, and non-threatening micro-pause. And then build from there.

Ready to learn how? Let’s go!

Why and how to pause

Dorsey Standish with Mastermind Meditate advocates for using the S.T.O.P. technique – Stop what you’re doing, Take 3 deep breaths, Observe what’s happening (thoughts, feelings, sensations), and Proceed in a way that supports you. This practice can be used during times of stress or transition from one activity to another to pay attention to your intentions.

Dorsey introduces the technique in a short meditation in the three-minute video below.

With practice, this one- to two-minute meditation can be done in as little as 10-20 seconds:

- Stop and come to a place of rest.

- Take some deep breaths, in through the nose, out through the mouth.

- Observe what’s happening within you – are there any emotions present? Or strong bodily sensations that you notice?

- Proceed in a way that will support you.

But to practice pausing, all you really need is five magical seconds

Kori from Kori At Home has this to say about finding peace in a five second pause, particularly in the context of parenting:

“But those five seconds are powerful and magical when it comes to our children. “

From Kori’s article, here’s the “simple magic” of the five second pause in parenting:

- We don’t need to have all the answers right away

- We don’t need to have perfect answers

- We don’t jump to conclusions

- We don’t answer the question we think our children are asking because we are actively listening to them

- We only answer the question they are asking

- We give our children the opportunity to gather their thoughts and verbalize

The five second pause in other contexts

- Wayne Turmel advocates at Management Issues for a five second pause during meetings, presentations, and training sessions because:

“If you can count to five slowly, you can probably get better results from your online presentations, meetings and training sessions.

The reason, strangely, is that we often don’t give people enough time to respond when we ask for their input, questions or comments.”

When the pause stretches to 3 or 4 seconds, there will have been enough time for it to sink in that you actually expect a response, and discomfort with the lack of a response becomes stronger. In the final second your audience members will be able to formulate a response, and if there is one to be had, someone will provide it around the end of the five seconds.

Once again, a lot can happen in that short period of time.

- Tanya Leigh at the School of Self-Image talks about the practical applications of a sacred pause in everyday life:

“And there’s that moment where you can engage in the familiar pattern of overwhelm, or you can take that sacred pause, take that five seconds to take a deep breath and say, wait, it can be different. It doesn’t have to be this way.

I can let the kids be crazy in the back seat, I can still have dinner that needs to be cooked, I still can have laundry that needs to be done, I can still have the job that I need to go to tomorrow, and yet I can respond to all of it so differently.

And those choices happen in the spaces of five seconds or less. And those choices are shaping your entire life.”

Five seconds is long enough to engage System 2 and your higher self.

Final thoughts

Learning to pause is a powerful way to ensure that “current” you does not accidentally foil “future” you’s plans and goals, and helps to focus your actions in the current moment on serving your true intentions.

The key takeaway if you don’t have time to invest in the moment? Even just 5 seconds?

When in confrontations, when feeling overwhelmed, when emotions run high, just stop – take a slow breath (in and out), think (engage System 2!), and then respond.

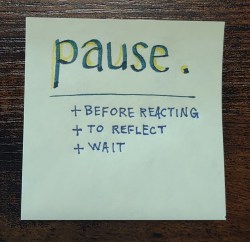

We can choose to pause:

- Before (re)acting

- To reflect

- To WAIT*

*WAIT = “Why Am I Talking?”

This comes from my friend and colleague Marissa Ryan, who learned it from the late, and great, Lloyd Jordan, her favorite mentor.

The idea is that before taking up the air in the room or in a meeting, we might pause to ask “Why am I talking?”, really listen to what’s going on, and consider what value we can truly provide to the conversation. If value, as perceived by the others in the group, is present, then by all means continue and contribute! But maybe pause for a moment, just to be sure.

One last way to think of this kind of pause… every time I go out the back door of my house to get to my office, I need to stop and think what state the alarm is in so that I don’t thoughtlessly trigger it. After setting off the alarm several times, I’ve trained myself to pause and think, usually with my hand on the knob, before taking the action of opening the door – what state is the alarm in? What time is it (because it’s programmed to turn on and off automatically)?

Then, and only then, do I turn the knob and open the door.

What do you do when you need to pause? What situations do you find challenging to insert a pause into?

“The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place” – George Bernard Shaw

My wife was in the process of telling me all about her day, in some detail, and if you’d asked me, I would have told you that I was listening to her.

But was I?

At one point she accused, “You don’t even know what I just said!” And I immediately replied that of course I do, and then proceeded to… well, show my ignorance.

We had a good laugh about it, since after we had established that I had forgotten what she said, she forgot what she had been talking about in the first place (bullet dodged). But it reminded me that I want to do a better job of listening, at home with my wife and son, and at work with my colleagues.

So what makes a good listener?

I believe it helps to be mentally and emotionally present for the conversation in the first place. But with presence established, what can we do to improve our listening skills?

I’m sure we’ve all heard reminders to use active listening for the best communication, and I think we think we know what that means, but just in case, let’s explore a bit. I know I needed to. 🙂

How to use active listening

My good friend Google turned up a seemingly obscure document that I think sums the practice up nicely, in the form of a teaching note from JoAnne Yeates for the MIT Sloan Communication Program.

From the note, an active listener:

- Looks and sounds interested in the speaker. Maintain good eye contact (but not too intense!). Try raising your eyebrows ever so slightly to indicate curiosity. Maintain a body position that shows attentiveness. If standing, ensure that your feet are pointed toward the speaker, not away from them. Use vocalizations like “mm-hmmm”, “uh huh”, “yes”, or “got it” to encourage them to continue.

- Adopts the speaker’s point of view. Try to see things from their perspective. Try to suppress any initial reactions and to hear and understand as if you were in their position.

- Clarifies the speaker’s thoughts and feelings. Limit your own talking to things that will encourage the most information and emotional content from the speaker, such as requests for additional information. Ask open-ended questions like “And how did you feel about that?”, or “Does that work for you?”. Check the accuracy of your understanding by asking questions that convey it, such as “So, you’re frustrated about that.”

Actively listening when communicating improves the chances that someone’s whole message can really get through. And wouldn’t you want them to do the same for you?

When communicating, assume the other is an alien… to decode/translate, you must put whole message into decoder. 🙂

Reflective listening

You might have heard the term reflective listening. I tend to want to conflate the two, and active listening is already applying aspects of this technique.

But reflective listening both enhances active listening and goes deeper to elicit as full a sense as possible of the speaker’s thoughts and feelings. It involves reflecting back to the speaker what you think they said in order to confirm (or correct) your understanding and encourage them to continue elaborating.

“Reflective listening is hearing and understanding, and then letting the other know that he or she is being heard and understood.”

There are five categories of skills related to reflective listening:

- Acknowledgements – “Uh-huh”, “mm-hmmm” and the like to show you are following the conversation.

- Reflecting content – the facts of the conversation.

- Reflecting feelings – how the facts make the person feel.

- Reflecting meaning – the essence of both the content and the associated feelings.

- Summarizing – repeating back what was said in different words to reflect the main points.

The reflecting process involves four steps:

- Taking in cues – While someone else is speaking, you are taking in cues from the areas of content (the words they are saying), feelings (stated or implied), and context (things you know or are aware of, other information you may know from the past).

- Sorting – sifting through the cues to arrive at the essence of what is being communicated.

- Drawing a conclusion – determining that essence and formulating a sentence to yourself about what the person is trying to say.

- Expressing the essence – sharing that conclusion back to check understanding.

Note that when sharing back it’s important not to simply parrot back what the other person said – they were there, they heard it… they said it. 🙂

It’s also important not to think of what you’re going to say next while attempting to focus on what the other person is saying and feeling.

Reflective listening is very different than providing what Neil Katz and Kevin McNulty call high risk responses (statements which are “likely to take the focus off the other and generate negative feelings”) in their paper on the subject.

These responses tell others that “they aren’t capable of doing for themselves, that there is something wrong with them, or that what they are saying is uncomfortable for you to hear.”

Some high risk responses to avoid:

- “I completely agree with you” or “I disagree on that point” – these introduce your own evaluations or judgments into the process and shift the focus to yourself.

- “What I think you should do is…” or “Why not take a different approach?” – these responses indicate your attempts to solve the problem for them, which is not necessarily what they are looking for.

- “Things will get better” or “I understand” – these attempt to divert the person from their problem, or prove that you’re listening without really doing so, respectively. They’re forms of withdrawing from the conversation.

Mindful listening

Mindful listening is a way of listening without judgment, criticism or interruption, while being aware of internal thoughts and reactions that may get in the way of people communicating with you effectively.

Mindfulness can be simply described as bringing attention to the present moment and experiencing it directly, using an open, accepting, and non-judgmental awareness.

Mindful listening is the practice of “bringing this full, moment-to-moment awareness to a speaker and their message.”

If you meditate, or use a meditation or relaxation app, you should be able to find meditations focused on the senses, and particularly on your sense of hearing.

Typically they’ll begin by getting you comfortable and relaxed, focusing on slow deep breaths and the feeling of those breaths as they enter and leave the body. Then, with eyes closed or partially closed, start to notice the sounds around you.

- Notice that you have a sense of directionality of sounds even with your sight removed from the equation.

- Notice qualities about the sounds… are they high or low-pitched? Are they pleasant or annoying?

- Now try to notice sounds without judging them. Just mentally label them (bird. refrigerator. car.).

- Notice what you can hear when you actually pay attention, rather than letting the sounds fade into the background as they often do when our brain isn’t paying attention to them.

True mindful listening, though, is a specific practice:

“Mindfulness encourages you to be aware of the present moment, and to let go of distractions and your physical and emotional reactions to what people say to you.

When you’re not mindful, you can be distracted by your own thoughts and worries, and fail to see and hear what other people are doing and saying.”

Author Charlie Scott, in his study, “Get Out of Your Own Head: Mindful Listening for Project Managers,” describes three key elements of mindful listening that we can use to improve our listening skills:

- To listen mindfully, first be present (this will be a theme, here).

- Pay attention to what is happening now, not what happened earlier or what might happen later. Bring yourself to the present moment.

- Next, try to cultivate empathy.

- Since we often see the world through our own experiences, putting yourself in someone else’s perspective, as with active listening, helps lower any barriers between you.

- This doesn’t mean that you need to agree with what the person is saying – just that they are speaking their own truth.

- It might help to envision yourself as a walk-on actor in the other person’s movie.

- Finally, listen to your own “cues”.

- Listeners approach a conversation with a Personality Filter that includes the thoughts, feelings, memories, and habits that make up their sense of self.

- Cues are what Scott describes as “the thoughts, feelings and physical reactions that we have when we feel anxious or angry, and they can block out ideas and perspectives that we’re uncomfortable with.

- Mindful listening can help us to be more aware of our cues, and allow us to choose not to let them block communication.

Mindful listening amounts to simply listening carefully and attentively – without judgment, without focusing only on what you’re going to say next, without coloring what you’re hearing based on your biases.

If you think that sounds a lot like active listening, you aren’t alone. 🙂

Final thoughts

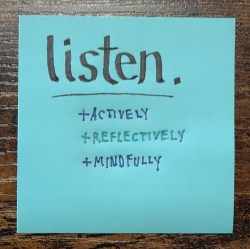

Here’s our card:

I feel that we owe it to the others in our lives to do our best to truly listen when they are trying to communicate with us.

When we listen to someone else, actively, reflectively, or mindfully, we are validating their perspective, regardless of our thoughts on the topic. And often it takes a little bit of effort on our part to get at what someone is really trying to communicate. But I think you’ll find that it will always be worth the effort.

I do know that the next time my wife asks me what she just said, I hope I’ll do a much better job of showing my attention and understanding her message, because I’ll do my very best to truly listen to what she is saying.

And if I screw it up again, I’ll just need to keep practicing. 🙂

But at least I hope she’ll know I’ve been trying.

Our attention is our most precious gift, and it costs us nothing… why not give generously?

Do you have any tips or tricks for listening better? Please share them in the comments below, or send us an email from the About page!