… and then keep asking. 🙂

“Ask why five times about every matter.” – Taiichi Ohno

How many times have you solved a problem only to have it rear its head again, possibly with only slightly different details?

Isn’t it nice when you solve a problem and it stays solved?

There’s a technique for root cause problem solving called “The 5 Whys”. It, like many Lean tools, is both simple and powerful. Going through the exercise of asking “why?” multiple times about the cause of a problem lets you dive down through its layers to find the true root cause that, when addressed, can solve the problem conclusively the first time.

And if it’s good enough for the Father of the Toyota Production System, I think it’s worth exploring a bit.

“The root cause is the core issue—the highest-level cause—that sets in motion the entire cause-and-effect reaction that ultimately leads to the problem(s).” – American Society for Quality

The practice when presented with a problem is to:

- Ask why it happened (or is happening), then write down the most obvious answer.

- Then ask why that thing happened, and write down that answer.

- Continue to ask why until you feel like you’ve reached an appropriate depth of root cause – five times is just a guideline, and you may arrive at your root cause sooner or later than that.

Note that the Five Whys isn’t as effective with more complex problems with more complicated causes – the Lean portfolio has other tools for those situations, such as the Ishikawa (or Fishbone) diagram.

But for many of life’s problems, by yourself or in small groups, this technique is a straightforward and effective problem solving tool.

Here’s an example to help illustrate: You get caught speeding.

Asking yourself why you were caught speeding, your answer is because you were late for work. So you write that down underneath:

| Got caught speeding. | Why? |

| Late for work. |

You ask why you were late for work, and then add that answer below:

| Got caught speeding. | Why? |

| Late for work. | Why? |

| Woke up late. |

… and so on, until you feel you’ve reached the root cause:

| Got caught speeding. | Why? |

| Late for work. | Why? |

| Woke up late. | Why? |

| Alarm clock didn’t work. | Why? |

| Batteries stopped working. | Why? |

| Forgot to replace the batteries. |

Now you know, and can solve, the real problem and not just a surface symptom.

Looking at it from a slightly different perspective:

So what if we did what we often do, and stop at the first level of why? Maybe we’d try getting to bed earlier at night as a possible solution… but would that solve the problem? Do you think it might happen again?

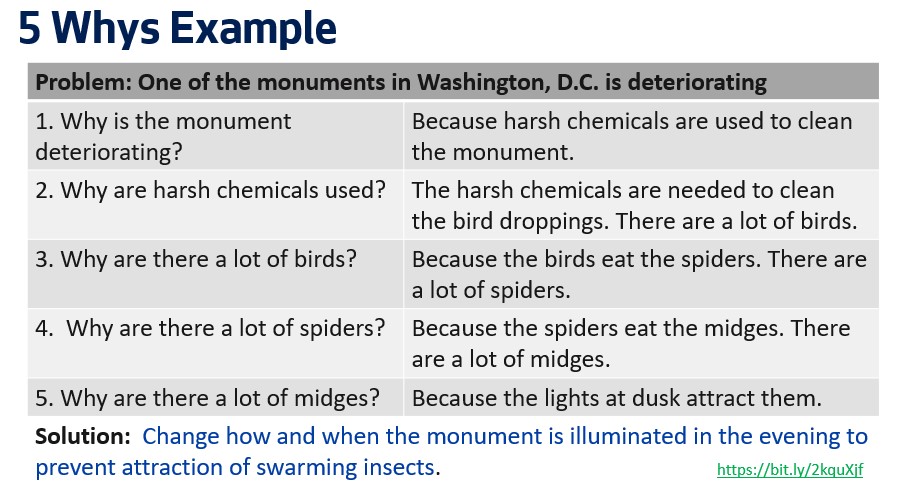

Here’s another frequently cited example problem: One of the monuments in Washington, D.C. is deteriorating.

What if we never went beyond step 1? We might change the chemical being used to one less harsh and see what happens… what do you think might happen, knowing the causes all the way down?

Here’s our card:

When you really ask why, you help to frame the problem properly and truly identify it. You can’t really solve it until you do.

Framing a problem properly helps solve its root cause

Here’s an example of how framing can help. Let’s return to Dr. Jody McVittie’s example, but from a different perspective.

A child wants a toy that another child has. They initially see their problem as “I want that toy” and might solve it by taking it. When they do, because after all it’s the logical solution, the other child protests, and conflict ensues.

What’s the root cause of the conflict? Is it that the first child wanted the toy? Why did they want the toy? Because the other child had it. Why did the other child have it? Because that child wanted it too.

Root cause is simple here. But when the problem becomes “both children want the toy“, many different solution options present themselves. What if they took turns? What if no one had it? What if they played with it together?

… and once again, we have calm. 🙂

Final thoughts

Channel your inner Taiichi Ohno and ask why five times the next time there’s a problem you need to solve.

What do you think about this technique? Does it seem simple enough to try with your child, or even your partner?

Modeling problem-solving with our kids is an engaging way to teach them how to solve their own problems.

Would you consider trying it on a work problem? Have you had any experience with this technique?

Let us know how it goes, we’re genuinely interested!

“The moment is not found by seeking it, but by ceasing to escape from it.” – James Pierce

I was helping my son do homework the other day. He has a number of challenges to such an endeavor, and it’s often helpful for someone to sit with him while he works. Partly to be available to answer questions that come up, but partly I think just as moral support.

He was working on his laptop, and even sitting next to him I had trouble seeing what was on the screen. But he was reading through the lesson portion of a study unit.

And my attention wandered. First to the work that I could be getting done instead of sitting quietly in a chair. Then, inevitably, to my phone.

After he asked a question and I needed for him to go back to everything he just read so I could understand the context, I realized that I hadn’t really been present with him in that moment. Not to the extent that I could have been. Not to the extent that I should have been.

Here’s our card:

What does “be present” mean?

One simple way to look at it is: You are present when your mind is where your body is NOW.

Awareness of and presence with what’s happening in the current moment is the key to mindfulness, which simply describes the ability to sustain awareness in the present moment, without judgment. So when you’re present, you’re being mindful. And when you’re mindful, you’re being present!

It really is just that simple.

How to do it?

Here are a few ideas:

- Use your senses for observation. There’s an exercise that is used by many to help cope with anxiety known as the 5-4-3-2-1 grounding technique. The goal of this exercise is to ground yourself in the present moment.

It works something like this:

- Find five things you can see. Just mentally name 5 things you can see in the present moment – hand, book, table, cat, light.

- Find four things you can touch. Notice touch sensations in your body without even moving – the feel of your pants on your legs, the pressure of your bottom in your seat, the coolness or warmth of the air. If you want to, touch something with your fingers, maybe something that you could see.

- Find three things you can hear. Just listen, and report to yourself what you hear – voices, the wind in the trees, the hum of an air conditioner.

- Find two things you can smell. You might be surprised that you can smell in the present moment. Does the air smell stale or fresh? Are there any scents you can pick up, like a perfume or food?

- Find one thing you can taste. Can you still sense the coffee you took a sip of a few seconds ago? No? Take another sip!

Using this technique, we’re reminded of what’s going on around us right now, and encouraged to return from whatever idyll had been occupying our minds.

In a hurry? Pick one or two of the senses to focus on.

- Ground yourself in the present moment, and whatever it brings – even if it’s uncomfortable, and especially if it’s pleasurable. Really sink into good moments and stay with them for a while before running off to the next challenge. You can try to do this by literally noticing the feeling in your body where your feet touch the ground.

- Focus on your breath. Wherever you are, it’s always with you. Breathe in slowly through your nose, focusing on the sensation of your lungs expanding and filling with air, or the air rushing into your nose. Follow the breath as it crests, focusing on the feeling of your lungs collapsing and expelling the breath through your nose. Just… notice the breath, don’t try to guide it. Stay with it for a few moments.

- Appreciate. Appreciate others, appreciate small things like the warmth of your tea or the smell of baked bread. Try to recognize small positives. Try to let small wins sink in before moving on to the next challenge.

- Cues/reminders. Some kind of audio or tactile reminder to bring yourself back to the present moment periodically from wherever you are mentally (or emotionally) at the time. I love technology for something like this. There are any number of apps that will let you know when its time to check in with the present. For example, the Calm app lets you set a daily meditation reminder, among others.

I personally have a script that runs on my work computer that chimes every 30 minutes to remind me to return to the present long enough to make sure there isn’t a meeting I’m supposed to be in or something. Not a simple thing for everyone to replicate, but that happens to be the tool I had available.

A simple vibrating alarm on your watch or phone can do the same thing more discreetly. It doesn’t need to be every 30 minutes to be effective.

- Practice. The more you do anything, the better you will get at it. Remember learning how to ride a bike? Remember how it felt at first, watching other kids ride their bikes, and imagining how amazing it would be? Remember how awkward it was once you first started learning? Remember what it felt like to get better at it and more confident but still careful, and then how it felt to be really skilled?

This is the Continuum of Change!

When learning any new skill we go through four phases:

- Unconsciously unskilled

- Consciously unskilled

- Consciously skilled

- Unconsciously skilled

… so practice your new skill every chance you get. You just won’t get any better unless you do.

Final thoughts

I know I need to keep practicing, every day. I know that when I returned my attention to my son and his homework, and really focused on being present with him, we had a wonderful working session and he got his assignment submitted.

The card reminds me to practice at work as well. When I’m in a meeting I owe the other attendees my best self, and that includes – even demands – my presence.

And it’s important to note that returning to the present moment isn’t something you do once and you’re good to go… you kind of have to keep doing it. But that’s okay. The more you practice, the better you’ll get, and the easier it will become to be present.

When we can be truly present in the moment we get to experience so much with our children and the people in our lives that we otherwise would have missed. Try to be present with yourself, but also be present with others – it is the most valuable gift you have to give.

Let us know in the comments if you have any other thoughts about favorite tools to feel present.

“The central motivation of all humans is to belong and be accepted by others.” – Rudolf Dreikurs (1897-1972)

Update

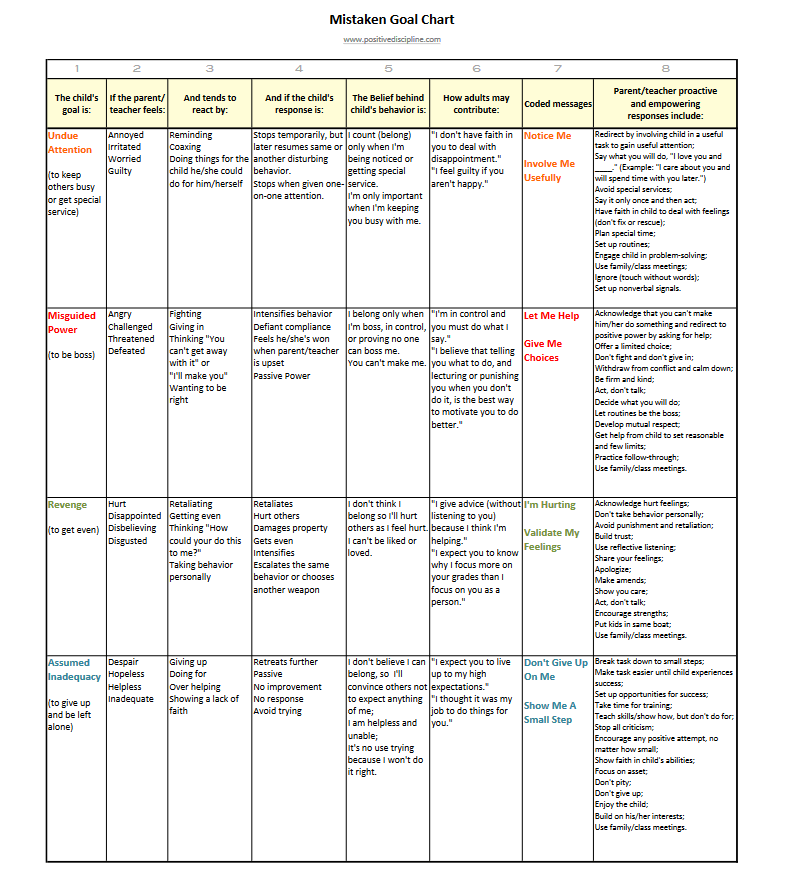

Its been a while since I checked in with the Positive Discipline source materials, and I recently found what looked to be an updated version of the Mistaken Goals Chart.

You can find more details about the chart here in my original post, but the new chart is copied below:

You might be thinking “Whoa… that’s a lot.” It kind of is… until you get a little practice with it.

Think of the chart as a magic decoder ring for your child’s behavior. We’ll walk through it with an example below.

I’m still in the process of comparing the updated version with the original version, but I do like the way they used colors to highlight the child’s mistaken goal and their hidden message to you, which is what you can choose to respond to rather than their outward display using the interventions in column 8.

So as a reminder and expansion, the chart looks like a lot – how do you use it? I couldn’t find a better explanation than Dr. Jane Nelson’s own:

“When children are misbehaving, they are speaking to adults in code. Learn how to break the code by following these steps:

1) Choose a behavior challenge.

2) Identify the feelings you have and how you react.

3) Identify the child’s reaction when you tell him or her to stop.

4) Use the Mistaken Goal chart to identify what belief may be behind your child’s behavior.

5) Try suggestions in the last column of the chart to encourage behavior change.”

If you’re still scratching your head (and you would not be alone!), please take a moment to jump over to learn more at the Positive Discipline site.

Parenting Interventions

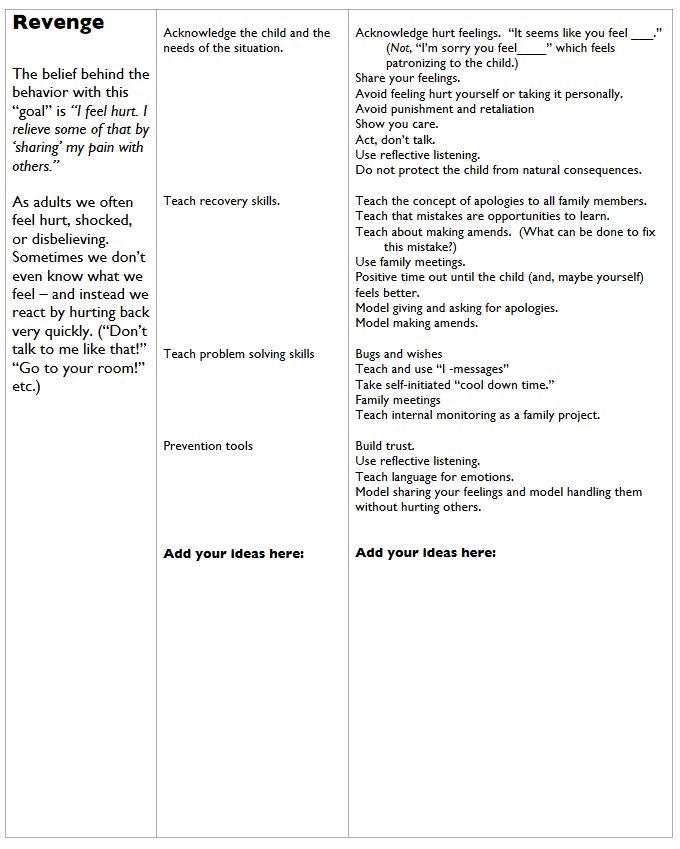

I’d like to take some time here to focus in on the Chart of Parenting Interventions by Mistaken Goal that Dr. Jody McVittie and Mary Hughes adapted from Jane Nelson’s work, and I’d like to challenge you to look at it from the perspective of interpersonal relations in general, not just between parents and children – I’ve applied this at some level to my relationships with my wife, my colleagues, and my friends.

This chart is meant to be used in conjunction with the Mistaken Goals Chart to identify in detail more specific things you can try in response to your child’s coded message as interventions in any conflicts resulting from a child’s behavior.

The Mistaken Goals chart helps you see the situation from your child’s perspective – the Interventions Chart further helps you figure out what to do about it.

Please do follow the link to print out the full chart, but I thought I’d zoom in on Revenge here:

Let’s imagine a scenario in which you and your child are arguing.

Your child says something hurtful and you want to react by hurting back, but after pausing by walking away to another room and reviewing the Mistaken Goals Chart you can imagine that your child is really trying to tell you that they’re the ones that are hurting, though they may not be consciously aware of how or why.

So you’ve followed the Mistaken Goals chart based on your feelings in the second column, and determined that your child’s mistaken goal in the first column is Revenge. How can the Interventions chart help?

- Look in the middle column for ideas. The first response is to “Acknowledge the needs of the child and the needs of the situation.” Sounds great… how?

- Look at the right hand column for specifics. You scan the list next to “Acknowledge the needs...”. The first intervention is to acknowledge the child’s hurt feelings.

You might say something like “It seems like you feel _____.” Observationally, but questioningly – the child will let you know if you guessed wrong, and either way you have one more piece of information that you might not have had before.

Sometimes the best action is inaction.

For example, other potential interventions are to “Avoid feeling hurt yourself or taking it personally” and “Avoid punishment and retaliation“, which can escalate the situation. Sometimes you can just walk away from a situation until both parties have had time to cool down.

In our scenario you decide to acknowledge your child’s feelings, so once you’ve both had your cooling down periods you seek out your child and do so. You also decide to use reflective listening while the two of you talk it out.

Okay, everything is great in the world again, you’ve navigated that crisis. But what if you’d prefer to avoid similar situations in the future? Is there anything you can do to prevent them?

Why yes there is!

Helpfully included for each mistaken goal is a list of prevention tools. Under Revenge, they include things like building trust, using reflective listening, and teaching your child language for emotions, which believe it or not they may not have – I know my own son does not.

I’ll try to focus in on other mistaken goals in other posts, because I think this combination of Mistaken Goals and Intervention Charts has become the most helpful resource I’ve used as a parent.

If you’d like to explore further, take a look at this Mistaken Goal Detective Worksheet, which will walk you through using the charts from a different perspective.

What’s interesting to me is the many interactions with other adults I’ve had – at home, in the workplace, in life – that this chart has proved at least partially helpful in navigating. Is there an age when Mistaken Goals stop applying?

I’d submit that there might not be… after all, all humans need to belong and feel accepted. I know that Rudolf Dreikurs focused his research on children, but I can’t find any similar research related to adults or even much older children.

Have you tried to use these charts in real life? How did it go? Let us know!

“We can be blind to the obvious, and we are also blind to our blindness.” – Daniel Kahneman

Daniel Kahneman (along with his partner, Amos Tversky) did groundbreaking (and in fact Nobel Prize-winning) work towards understanding (and even defining) what he called “behavioral heuristics” and “cognitive biases”.

A heuristic is simply a mental shortcut that allows your brain to avoid doing actual work. One famous example is the availability heuristic:

‘The availability heuristic is a mental shortcut that occurs when people make judgments about the probability of events on the basis of how easy it is to think of examples. The availability heuristic operates on the notion that, “if you can think of it, it must be important”‘. – Wikipedia

A cognitive bias is a recurring error in thinking that applies itself even if you are aware that you have it. According to Joe Hitchcock at Inside BE:

“Cognitive biases influence the way we perceive and interpret information. They can cause us to make decisions that aren’t based on facts and behave in ways that don’t follow logic.”

An example of a cognitive bias is the framing effect – people react differently to something depending on how it is presented to them:

“While doing your groceries, you see two different beef products. Both cost and weigh exactly the same. One is labeled “80% lean” and the other “20% fat.”

Comparing the two, you feel that 20% fat sounds like an unhealthy option, so you choose the 80% lean option. In reality, there is no difference between the two products, but one sounds more appealing than the other due to the framing effect.” – Kassiani Nikolpoulou

Kahneman explores heuristics and cognitive bias in great detail in his book, “Thinking, Fast and Slow“. He also posits a model of human cognition that consists of two disparate “systems”, as a shorthand for the details of the various neurological components that they consist of.

System 1 is fast. Very fast. And instinctive. That often has its advantages.

System 2 is slow. It costs more energy, but delivers deeper, more logical results.

System 1 is kind of the default pilot as we go about our day, and whenever we put our thinking caps on, we can access System 2. Which is fine.

Except…

System 1 likes shortcuts, so heuristics and biases are its bread and butter. It does not under any circumstances care to engage System 2 if it can at all help it. When we talk about having biases in general towards something or away from something, these biases are intrinsic in our wiring, so the challenge is to:

- Be aware of System 1 and the decisions it is making on your behalf.

- Find a way to short circuit System 1 and engage System 2 when it really matters.

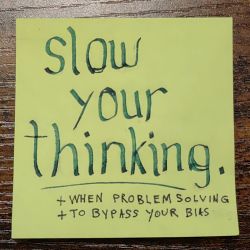

Let’s pause for a moment and look at our card:

To slow your thinking is to consciously and purposefully engage System 2.

When problem solving – at work, with a partner, with your child – it’s helpful to slow your thinking to make sure that you are addressing the right problem and that you don’t approach it with any built-in biases.

Once we’re aware of our biases, can we change them? Not this kind. Not even if you know about it. This kind of bias is part of you.

But… with attention and intention you can work to bypass your bias.

Slowing your thinking can help.

But remember that engaging System 2 is effortful and takes energy, so it’s important to take care of yourself and rest and relax when you can.

Have you had any luck trying to slow your thinking, maybe at a time when it really mattered? Let us know how it went in the comments!

“We are doomed to failure without a daily destruction of our various preconceptions.” – Taiichi Ohno, father of the Toyota Production System

Recently I’ve been eyeing the meadow that in theory is supposed to be my backyard, watching it mark its slow transition from winter slumber into something I need to mow, and not particularly looking forward to the prospect, so I thought a bit about why that was. I like being outside. Mowing isn’t particularly hard for me.

I thought about the process of mowing the lawn. I thought about getting the mower out of the shed, getting a battery from the charger and installing it, awkwardly maneuvering it down the rocky terrain to the backyard, realizing I didn’t pick up the branches from the enormous cherry tree in the yard, stopping to do that, then finally mowing the yard and reversing the process to put everything away.

If I think about it before I try to mow, it’s obviously wasteful to pick up sticks after I start, so it would probably make sense to do that before. And there doesn’t seem to be any value in wrestling the machine over rocks to get it to the place it needs to be used in. Maybe I could store it somewhere behind the house?

In Lean manufacturing, or the Toyota Production System, the concepts of value and waste are inherent and of special significance.

“The slower but consistent tortoise causes less waste and is more desirable than the speedy hare that races ahead and then stops occasionally to doze.” – Taiichi Ohno

Let’s explore a little more deeply into what I mean when I talk about value and waste.

In Lean, value-added activities are contingent upon three things being true:

- The step must change the form or function of the product or service

- The customer must be willing to pay for the change

- The step must be performed correctly the first time

I could summarize this as:

If it is transformative, desirable, and correct, it adds value. Anything else is waste and should be reduced or eliminated.

The ideas of adding value and eliminating waste are at least undercurrents throughout Lean philosophy. I’m sure I’m not the first to suggest that these concepts are transferable to other domains, such as your daily work, or even parenting.

Think about value and waste in your relationships – what things bring you closer and what things don’t? Wouldn’t it be nice to eliminate those things that don’t add value or improve your connection and focus on the things that do?

Think about the processes you follow to complete your daily work – are there any opportunities to reduce or eliminate steps that don’t enhance the value of what you are delivering?

In a relationship between any two people – parent and child, two partners, two colleagues, two friends – some wastes are relatively easy to identify, and others might take deeper introspection and retrospection to recognize.

Can you think of any wastes in your relationships?

I can.

Here’s one I recognized just the other day – if I say or do anything that in any way might threaten my wife’s confidence in cooking, or that even peripherally could be interpreted to question her ability to cook, it most certainly will not add anything of value to our relationship, and can only introduce defects. It fails the desirable check, and it arguably isn’t correct either. I decided to make conscious choices to support and reinforce her intrinsic value as a chef, rather than for example voicing any differing opinion I might have regarding what to add to a dish to make it better (lesson learned the hard way).

Having a preoccupation with eliminating or limiting waste, Ohno identified and described a set of basic lean wastes, which have been refined and expanded over time. Naturally they are oriented towards a manufacturing environment, but they can be placed within the context of other domains as well.

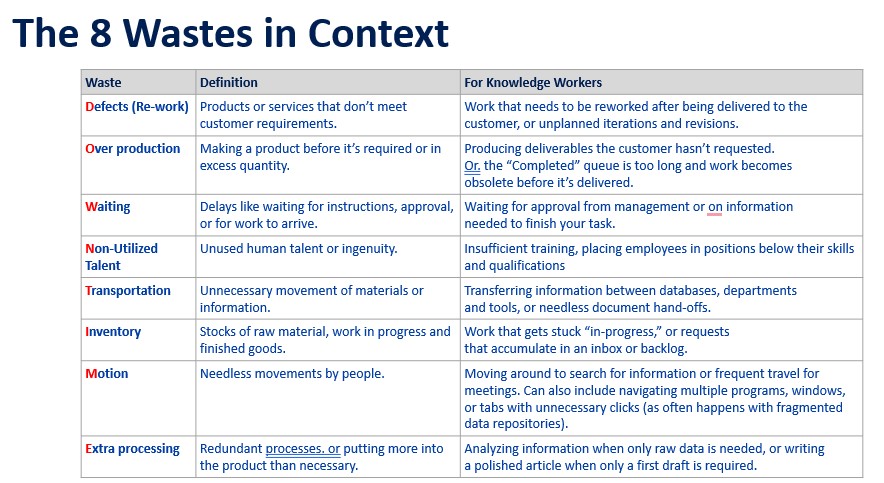

For example, here’s a chart of the eight Lean wastes and their context for knowledge workers (office workers, software developers and testers, etc.):

(I’m working on a “For Parents” column and will add it here when it’s ready.)

Scanning the table, you may already be able to relate some of these wastes to your own situations. Looking at “Defects“, I can imagine a product or service that doesn’t meet customer requirements being a meal I made for, but which was not appreciated by, my son. How to eliminate that waste? Maybe I’d involve him more in the meal planning and preparation process so that he has more of a stake in the meals.

Because I suppose it’s now tradition, and just to make it official, here’s the card:

No details to expand on… it is what it is.

Viewed through this lens, my lawn mowing process can be improved by addressing the waste of Non-Utilized Talent (my son)… comparatively I am a bit over-qualified for the position of lawn mower, and since it’s an opportunity for my son to learn and improve a work ethic, it actually adds value to him and to our relationship.

What wastes can you find in your processes or relationships?

“Be like a duck. Calm on the surface, but always paddling like the dickens underneath.” – Michael Caine

Dan Siegel has a short two-minute video where he talks about a model for the human brain called “the brain in the palm of your hand”. You can watch it here:

Siegel describes bringing your thumb in towards the center of your palm and then folding your fingers down over it. Your thumb represents the limbic system of your brain, or your reptilian brain, that legacy of evolution that is responsible for processing and regulating emotion and initiating the fight or flight response. Your fingers represent your cortex, that higher level of function that is the seat of reason and cognition, and that has the role of regulating the limbic system.

When emotions run high or the fight or flight instinct is triggered, Siegel illustrates by straightening his fingers to expose his thumb (“flipping his lid”), showing that the limbic system is now in control – thinking, reasoning, calming, all become challenging if not impossible.

So that’s part one of what we’re exploring today.

Part two involves something called “mirror neurons”, which Dr. Siegel also helpfully explains here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tq1-ZxV9Dc4

Mirror neurons are present in all of our brains, and can be described like this:

“Mirror neurons represent a distinctive class of neurons that discharge both when an individual executes a motor act and when he observes another individual performing the same or a similar motor act.” – National Institutes of Health

These neurons fire not only when I hit a baseball, but also when I see you hit a baseball… is that not absolutely amazing?

It gets better. Mirror neurons can fire for emotional states as well. That’s why if I see someone laughing happily I might smile myself. Or if I see someone yelling angrily…

So bringing together part one and part two – and you probably already see where I’m going with this – when I flip my lid, the thinking and reasoning part of my brain has less influence, and if I flip my lid at my son, he’s likely to flip his lid right back. And both of us will need a cooling down and repair period before we can even begin to interact reasonably again.

Think about how it feels when someone – your child, your spouse, the guy that thinks you stole his parking space – “flips their lid” at you… are you able to observe dispassionately? Or are you inclined to respond in kind?

Think about how it must feel for them when we flip our lid at our kids.

Let’s pause here for a moment to take a look at our card:

When dealing with co-workers, children, friends, family, maintaining a calm outward demeanor helps to ward off countless potential disagreements and clashes before they can even get started. You can use mirror neurons to your benefit… the calmer you remain outside, the calmer others are encouraged to be, inside and out, and the less likely they are to flip their lids in the first place.

Always be aware of the consequences of flipping your lid. And do your best to exude calm outwardly, regardless of the state of your own lid, over which you ultimately have no real conscious control.

Finally, if you do flip your lid at someone, all is not lost… you can always repair.

How do you maintain calm when everyone around you is flipping their lids? How do you get calm when your own lid is flipped? Let us know what you do in the comments, and I’ll share out your ideas in a future post.

For now, see if you can find a way to separate yourself from the situation until you or they have had a chance to make themselves calm. Reasonable discourse is simply not possible with flipped lids.

Another idea (if yours is the lid that flipped) is to try to purposefully engage your cortex (your fingers from “the brain in the palm of your hand”) by doing something that requires it by spelling things backwards, listing facts, or doing mental math – try counting backwards from 100 by 7s, for example.

Finally, if the other person has flipped their lid, there are a few things you can try that might help:

- Use your mirror neurons. The more you model calm and stay connected, the easier it is for someone else to calm down. So lower and slow your voice, and engage your cortex.

- Acknowledge feelings. Use few words, and a calm, empathetic tone.

- Invite them to take a break. This works best as a genuine option rather than a command.

- Simple tasks may engage their cortex. You might ask them if they remember how to spell someone’s name, for example.

- Ask for their help. Especially if they’ve already begun to de-escalate but aren’t quite there, change the subject and ask for their help: “I can tell it’s not a good time to talk about ‘x’, but would you be willing to help me with ‘y‘”?

Again, please let us know how you calm yourself in the comments… we’re always looking for new tips!

“It is not enough to do your best; you must know what to do, and then do your best.” – W. Edwards Deming

In many ways my atomic sticky notes (really need a new name for them, and I am fully open to suggestions) evolved out of a Lean manufacturing scheduling system originating in Japan, invented by Taiichi Ohno, called kanban.

I’ll add some more details here about kanban later because it’s fascinating, but for now it’s important only to note that it’s evolved to become a scheduling tool in Agile software development and even a personal productivity framework, as we’ll explore.

Let’s take a quick look at our card:

The premise is simple… first, visualize your work. Then, limit your work in progress.

That’s it. Those are the rules of Personal Kanban.

A light and flexible framework

All else is flexible and mutable to customize as you desire. Visualizing work enables better cognition, conversation and collaboration where needed and is just often the most human way to process and convey information.

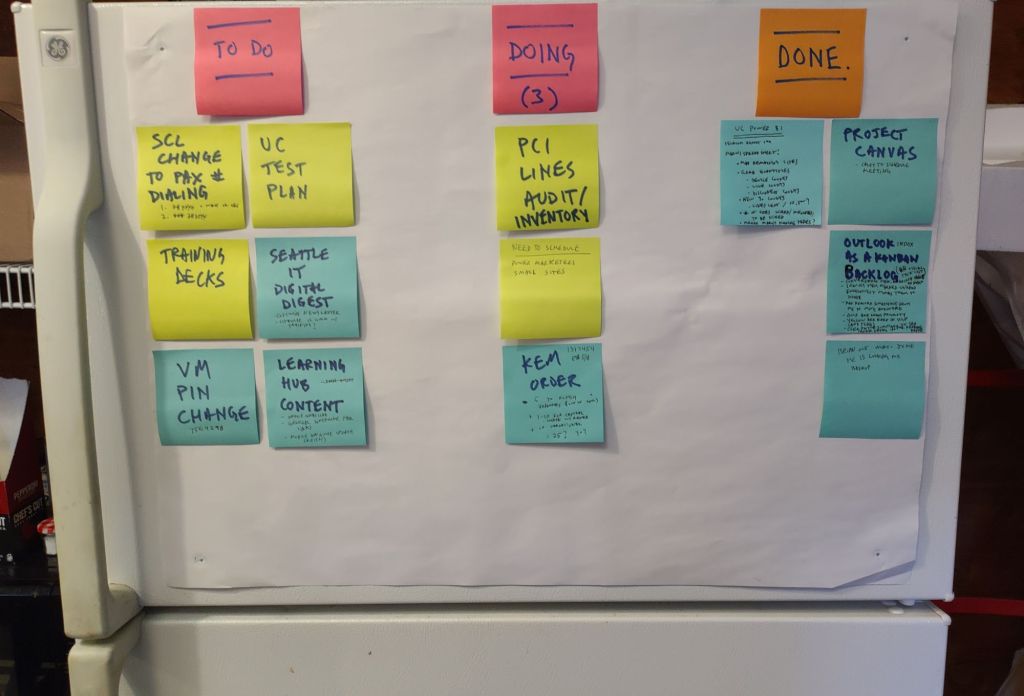

Create a few columns on a white board for “To do“, “Doing“, “Done“, and add tasks on sticky notes to the appropriate columns.

Tasks move from left to right across the board. As tasks progress, physically move the appropriate sticky note to the next column, then pick something to replace it from the column to its left.

Take a moment to notice that the tasks here are a mix of work and personal… the fiction that work and life are separate things that can be balanced should be rejected, because really, do you stop thinking about life while you’re at work and vice-versa?

Limit your work in progress

Limiting the number of items in the “Doing” column turns the sticky notes into a kind of currency that you can choose to spend in real time. Finishing an item on the board moves it from “Doing” to “Done“… now, what will you pull from “To do” to work on next? Something quick? Something easy? Something high priority?

A scalable system

The system is infinitely adaptable and scalable. Just map your particular value stream onto as many columns as you need. For example, a writer might have a value stream that looks like “Ideas“, “Draft“, “Edit“, “Publish“.

| Ideas | Draft | Edit | Publish |

One of the benefits of using a kanban system for task and process management is its scalability – it can be used by an individual or by large global teams, thanks to a cornucopia of online tools that let you share boards and collaborate with others.

But on a personal or small team level, all you need to throw up a quick kanban board are a bunch of sticky notes and something to write with. I’ve created impromptu boards on my walls and refrigerator at home, for example.

Notice that the “Doing” column has a limit of 3 tasks that can be in progress at any time. So only by moving a task to the “Done” column can I pull a new task into “Doing” from “To do“.

Notice also that the notes are different colors, and some have details included. These are additional ways to convey meaning visually, if you’d like to use them. In this case orange and pink are column titles, yellow designates one project I’m currently working on, and blue indicates another.

What now, and why here?

For a true introduction to Personal Kanban, you can learn more from creator Jim Benson in this short video:

You can also find his Personal Kanban book, written with his frequent collaborator Tonianne DeMaria, on Amazon.

But the reason that I bring it up here in a parenting blog is twofold:

- A little thing like, I don’t know, organizing your life can offer great rewards in your relationships with your children, and…

- It is a *wonderful* thing to teach your children to help them organize their own lives.

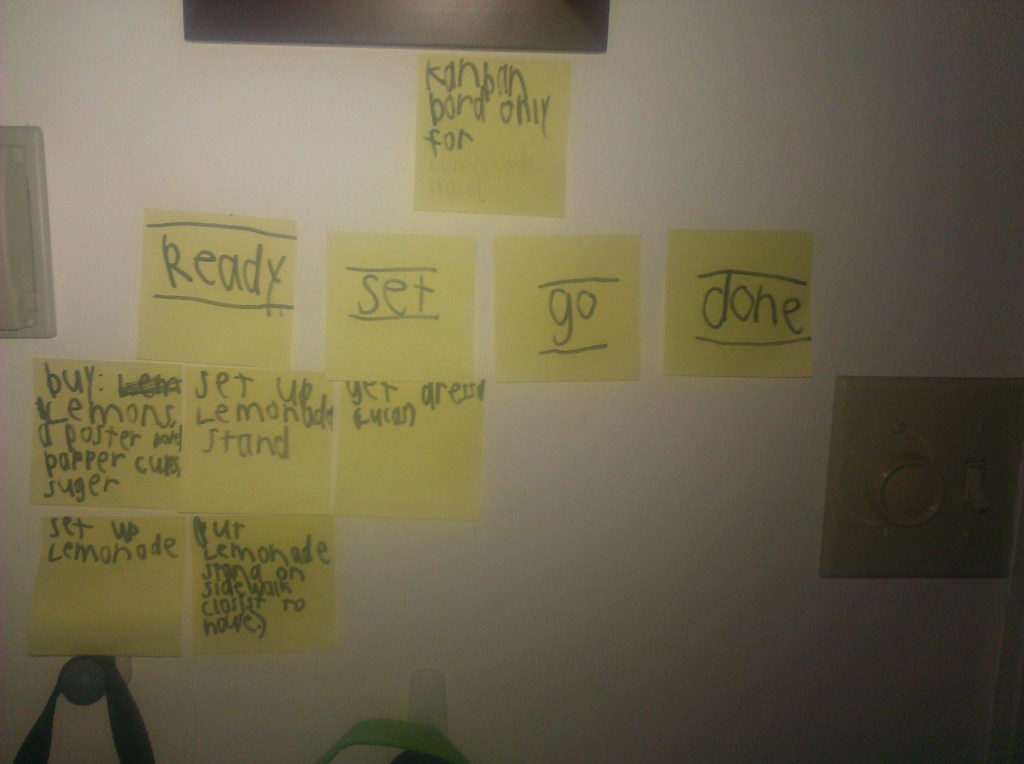

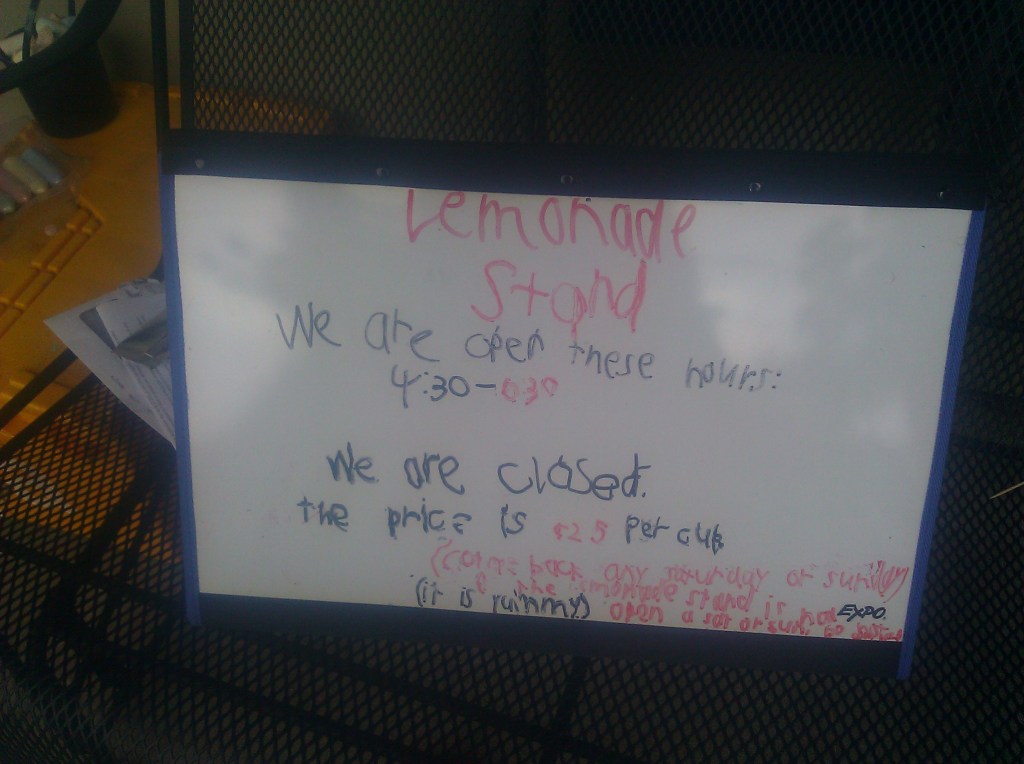

I’m looking frantically for a picture (edit: found it below!), but one of my fondest memories with my son is teaching him how to use kanban and helping him create a kanban board for his first lemonade stand. His value stream was “Ready“, “Set“, “Go!” and he had sticky notes with tasks like “buy lemons” and “make a sign”.

At the top, it says “kanban bord only for lemonade stand”

Final thoughts

I’ll add more details here later, but for now, please at least explore the Personal Kanban video above. You may be glad you did. 🙂

From the copy for the book:

“Personal Kanban asks only that we visualize our work and limit our work-in-progress. Visualizing work allows us to transform our workload into an actionable, context-sensitive flow. Limiting our work-in-progress helps us complete what we start and understand the value of our choices.

Combined, these two simple acts encourage us to improve how we work to balance our personal, professional, and social lives.“

And please reach out with any questions about how to apply this framework to your work and life tasks.

| To do | Doing | Done |

What is your value stream?

… when you really need it.

See the post “Shift your perspective.” for the first in this series exploring my atomic (in the sense of a thought or idea being reduced to its most basic essence) sticky notes. My hope is that these concepts are universal and applicable across multiple domains, including work, life, and parenting.

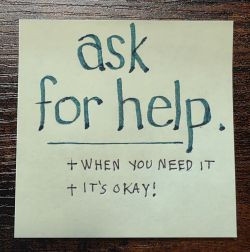

Next up is “Ask for help.”:

Pretty straight-forward, this one, but important to highlight, especially in the context of parenting.

At the detail level, we have:

- When you need it

- It’s okay!

If you’re someone for whom asking for help does not come naturally, this can be challenging, if not intimidating. It’s a matter of degree, isn’t it? We all know people that will ask for help at the drop of a hat, regardless of its impact on anyone else, and regardless of the level of effort required to help themselves. We don’t want to be that person. It’s natural.

Especially when it comes to parenting. We can be very sensitive to the external perception of ourselves as parents and our fitness for the role. “What kind of parent am I if I can’t figure this out?”, we might ask ourselves from time to time. Or more pertinently perhaps, “What will they think of me and my parenting skills, or lack thereof?”. So many obstacles to asking for help.

But when you really need it, when you really, REALLY need it, please find someone trusted and reach out to them for help or advice.

Someone might be a spouse or parenting partner (though if they have a markedly different parenting style you might not *want* to – consider it anyway) or a relative or a friend or a community forum of some kind.

Help might be picking up your kids from practice, or making a meal for your family from time to time.

Advice might be how to deal with a teenager that is acting rebelliously.

If it helps, apply some measure to your amount of need, but if you do, please ask for help when you need it… and I think you know when you do.

And you can “ask” for help by referring to a trusted resource, related to whatever current problem you’re needing to solve.

How to ask for help

From Debbie Sorenson at Psyche, here is a list of things you can do and consider as you prepare to ask for help.

First, check for assumptions you might have about asking for help:

- Negative associations – you may not want to be thought of as someone that can’t help themselves, for example.

- Self-criticism – you might feel that asking for help would make you seem weak or helpless.

- Concerns about how you will be perceived – you might worry what others might think of you if you ask for help.

- Overestimating the likelihood of rejection – because why would anyone help?

Decide to ask for help. As you do, you may want to consider the bigger picture – what is most important in this moment? And long term, will asking for help further or hinder your goals for yourself or for others, especially your child?

Then decide who to ask. Consider who is in the best position to help you. In some cases that might be a professional of some kind, especially if you’re really struggling emotionally. I know that’s a barrier for some. Try to follow the process with them. But consider relationship dynamics with your friends, family, and colleagues, and try to find someone that you can trust to respond compassionately.

Debbie reminds us here to be compassionate with ourselves first, and really explore the emotions that might underlie any continued reluctance. Do you feel guilty or ashamed about asking for help? Are you afraid you’ll be rejected? Notice those feelings and acknowledge them, but try to see if you can practice watching them as an observer.

Use assertive communication skills (“I’ve been struggling with ____, would you be willing to help?“) and be clear about what it is that you need. Other examples Debbie suggests are:

“Could you help me out by ____?”

“I was wondering if you could do me a favor and ____.”

“Could you please ____ for me next Tuesday?“

If someone agrees to help, accept it, and share your gratitude. If they don’t, it doesn’t mean you won’t be able to get the help you need… it’s just time to consider other options.

Resources

Here is a list of Positive Discipline parenting resources. It’s separated into products, articles, and classes. If you click on the button for Parenting Articles, you will be taken to a list of foundational Positive Discipline concepts to explore. It’s a welcoming and encouraging philosophy and tool kit, and I hope you’ll explore it further.

My personal favorite Positive Discipline book is “Positive Discipline A-Z” – it’s chock full of solutions by parenting challenge and has been a huge source of self-help for me almost daily.

Here also is a link to the resources page on this site.

And if you need more details about how to ask for help, please read Debbie’s full article. In the links she shares at the end is a particularly wonderful and engaging TED talk from Heidi Grant on the subject.

Please reach out for help when you need it. In whatever way you’re most comfortable with. But no one can do this alone.

Contact us

Please share anything that comes to mind, whether it’s feedback on the website or its layout, suggestions about the content, or anything at all that comes from your perspective and we will get back to you as soon as we can.

Any messages are considered confidential (the message is sent to tim@sharingperspectives.com) and will not be shared under any circumstances.

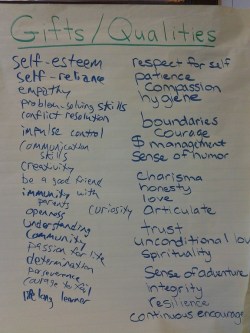

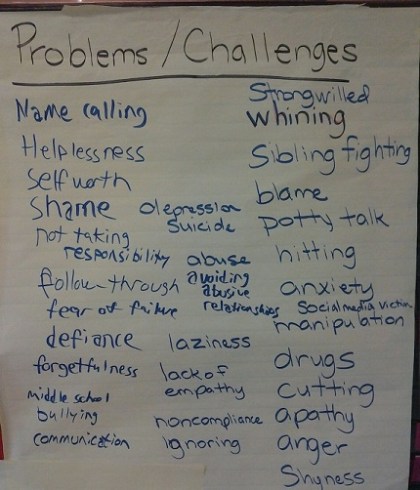

There are two main goals we’re aiming for with this exercise:

- We bring the focus to long-term parenting. It’s so easy to lose track of long-term goals when everyday life happens, and while practicing Positive Discipline certainly helps improve relationships and reduce battles on a day-to-day basis, it does so through the lens of the long view.

- We want the parents to truly understand that they are not alone. Not in the problems and concerns they are faced with, and not in their hopes and dreams they have for their children.

The question is – how do we get from the first list to the second?

And of course, that’s why we’re all there. To learn and practice the skills to work through our challenges and impart these long-term gifts to our children.

This is a great illustration of the focus in these classes on experiential activities and group brainstorming. These lists aren’t our lists as facilitators. These lists are our lists as a group of parents that want to do our best.

We don’t have to be perfect. It’s not good for our kids if we’re perfect, because they’d miss the opportunities to see us make mistakes, learn from them, and clean up after them.

They’ll learn from that. They’ll learn a LOT from that.

These lists are posted on the wall for every class, as reminders of areas of focus for the tools and skills we discuss and practice, and of the ultimate goals of all of this effort and heartache and joy and frustration and gratification and helplessness and effectiveness and learning and practice.

I can’t wait to look back on these lists at the end of the seven weeks and see if it looks or feels any different.

An experimental post

So the blog is called “Sharing Perspectives”, and there’s a reason.

I propose that the most urgent and vital thing we can learn as sentient beings is to think and feel from another’s perspective.

Perspective is an interesting word to me, full of meaning and implications and possibilities, but the point I’d like to make is that, with enough practice, we can truly imagine ourselves in someone else’s place, either mentally or emotionally, which allows us to cross a crucial gap from sympathy (or even apathy) to empathy.

How is empathy different?

“Empathy is our ability to understand how someone feels while sympathy is our relief in not having the same problems.”

That comes from a group called Psychiatric Medical Care, who explore the differences in more depth in an article posted here. But what I’d like to focus on is the idea that sympathy causes separation, while empathy fosters connection.

From the article:

Brene Brown describes sympathy as a way to stay out of touch with our own emotions and make our connections transactional. Sympathy puts the person struggling in a place of judgment more than understanding. A person seeks to make sense of a situation or look at it from their own perspective.

Further:

Empathy is defined as “the feeling that you understand and share another person’s experiences and emotions” or “the ability to share someone else’s feelings.” It is looking at things from another person’s perspective and attempting to understand why they feel the way they do.

Seeing from another’s perspective makes us more empathetic – not just towards one person, but just a little towards people in general – which fosters connection and understanding.

How can this help?

So what to do with this knowledge? How can we learn to see from another’s perspective? How can we teach our children to?

While some people naturally possess empathy, it’s also something you can learn, develop, and even teach.

To quote one of my mentors:

“The life skill of being able to look at things from more than just your point of view can be taught by simple modeling and observations.” – Dr. Jody McVittie

She uses the example of a child wanting a toy that another child has. The first child unconsciously frames their problem as “I want that toy.” The obvious solution to which, of course, is to take it.

Saying to the child “It looks like you both want that toy” challenges them to re-frame their problem as “we both want that toy”… and suddenly other potential solutions present themselves.

Watch their face as understanding dawns… they want the toy, the other child also wants the toy, and the wheels turn to generate a solution to the newly framed problem.

What if they took turns? What if they played with the toy together?

What if, instead of feeling a need to take another child’s toy away, the first child decided on their own that their solution would be to share?

What would they learn from the situation? And what did they just practice?

Can you imagine if everyone in the world could easily adopt any and every other person’s perspective?

Could there still be violence and hunger, destitution and excess? Wouldn’t this empathy and connection and compassion and understanding foster horizontal relationships between everyone rather than hierarchies and classes?

If we scale down our ambitions just a bit – only for now – we can practice seeing and teach seeing from other perspectives as a way to create, strengthen, and deepen our interpersonal relationships – including those we have with our children.

Especially with our children.

… and now for the experimental part!

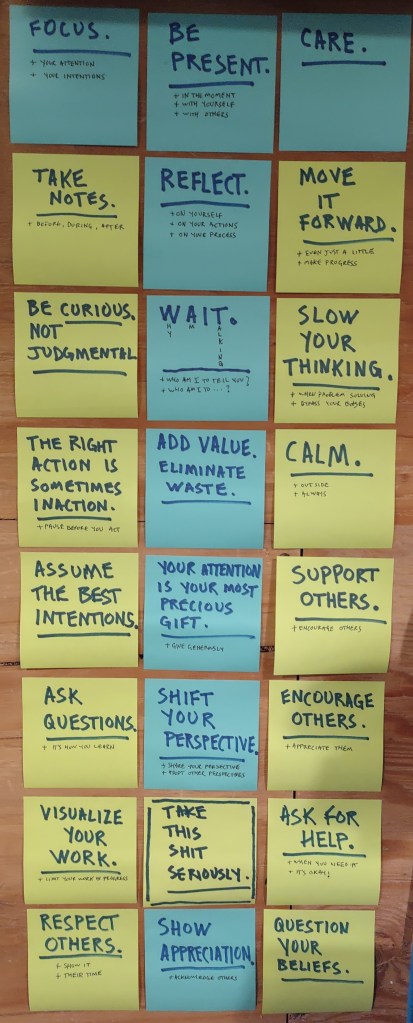

So I have kind of a thing with sticky notes. There’s something interesting to me about the implications inherent in the limited format, the portability, and the physicality as a space to keep track of things.

I’ve been using Personal Kanban, which uses sticky notes to move “things to do” through your own personal value stream, for several years now as a way to visualize my work and life tasks. At some point I started using sticky notes to capture various reminders and thoughts and musings as well, and eventually my house was pretty well pasted with them.

I even started to create artwork using Post-It notes and Sharpie pens. I am deadly serious about that – I participated in an art show at a local gallery in Seattle.

A theme emerges

A theme started to emerge, but I wasn’t sure what it was, or what to call it… some of the notes started feeling more significant than others. Reminders to myself, from myself, of lessons I’ve learned here and there. Ideas reduced to an atomic form. These started to claim their own space on the wall of my home office.

They were inspired in part, I think, by Dr. Rick Hanson‘s work in his book Just One Thing: Developing a Buddha Brain One Simple Practice at a Time, in which he encourages us to explore simple practices, grounded in brain science, positive psychology, and contemplative training, for just a few moments every day.

In the beginning there were maybe 6 or 8 cards.

Currently there are 24.

UPDATE: November 24, 2024 – I’m down to 15 cards, that each have a published article behind them. This is what they look like now:

I still don’t know what to call them… originally I thought of them as goals and thoughts to keep in mind while working. Then I wondered if they were some kind of values list, but that didn’t seem right either. I’m currently thinking of them collectively as “Guidance”, because it occurred to me that all of the best wisdom and advice I could possibly give my son was there – this is no longer a work list, it is a life list.

Shift your perspective.

I’d like to start exploring these thoughts and what’s behind them in a series of posts. Since the title of this post is “Shift your perspective.”, that’s the one we’ll zoom in on a bit.

Each note title may have additional detail below it, usually extensions to or clarifications of the title. In this case, the detail level includes:

- Adopt others

- Share yours

“Adopt others” is fairly well covered above, so let’s finish with a quick look at “Share yours“.

As it turns out the inverse of the above is also true – not only can you strengthen your connections by adopting other perspectives, you can help others strengthen their connections with you by sharing your own perspective.

Sharing your perspective allows others to have a better understanding of where you’re coming from and takes some of the mystery out of interpersonal relationships – and hopefully will encourage others to do the same in return.

What’s your perspective?

Contact us

Please share anything that comes to mind, whether it’s feedback on the website or its layout, suggestions about the content, or anything at all that comes from your perspective and we will get back to you as soon as we can.

Any messages are considered confidential (the message is sent to tim@sharingperspectives.com) and will not be shared under any circumstances.