Lucas was hurting the cat in a particularly worrisome way. We’d had talks several times that day about how to treat her. I truly felt scared that she would be seriously injured.

I yelled “Stop it!”. Loudly. Reeeeaaallly loudly.

He left the room with his hands over his ears, saying, “I’m ignoring you!” He came back in and started hitting me with his jacket. I told him I was sorry that I yelled at him, and that I had been really worried about the cat. He told me he did not accept my apology. I told him I couldn’t stay and be hit, so I needed to go to another room for a while. And I did.

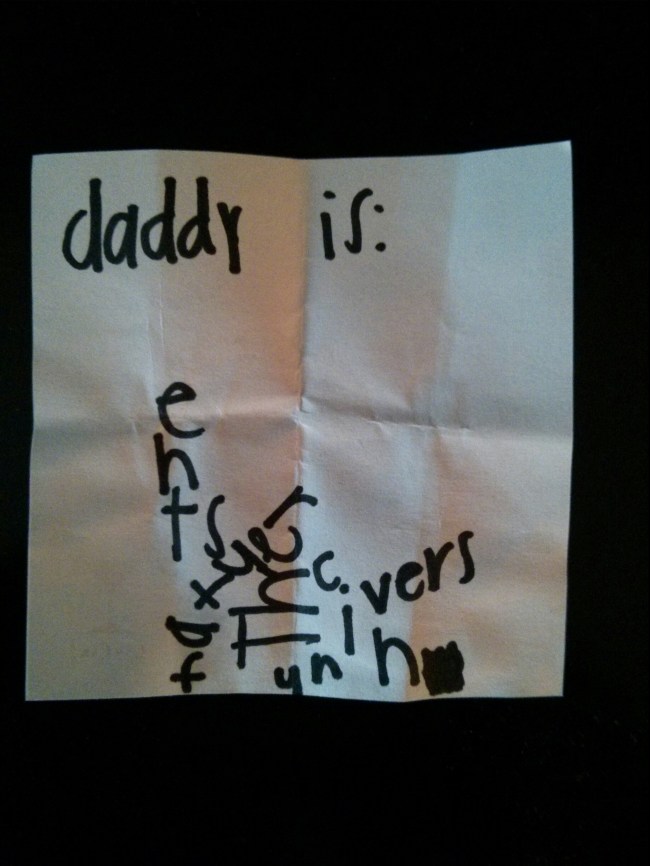

When I came back, I busied myself in the kitchen, and he was quietly writing something in the living room. I went over to him again, and said, “Hey, buddy, I’m really sorry I yelled at you. I really was very worried about the cat. Let’s work together to figure out how we can keep the cat safe with no yelling.” This time he said, “I accept.” He added, “…and now I don’t have to finish writing this.” I looked at the paper in his hands, and saw “Daddy is:” at the top, and below he had written in a kind of crossword style “stupid”, “dumb”, and “mean”. Ouch. I told him I was really glad that he didn’t need to finish it.

Then, he told me to hang on, and not watch him. After a few minutes he showed me he had created a code, and that I should try to solve it. The letters were jumbled and turned around, and with a few clues, I was able to solve it.

It said, “Daddy is: the best father in the universe.”

This is a wonderful example of the power of repair. A handful of words, and I went from being a smudge of bug guts on the bottom of a shoe to being the paragon of parents everywhere. But nothing changed about me. He felt disconnected from me, and then he felt reconnected with me.

Repair in the Positive Discipline context is a specific process, and it goes like this:

- Re-gather: Make sure you have both cooled down and un-flipped your lids. This may take a little while, or as much as a few days.

- Recognize: This is internal to yourself. Notice what it was that you did to create the problem. Even though another person may have contributed, this is to take responsibility of your own part in what happened.

- Reconcile: VERY briefly acknowledge your mistake, and express your regret (“I’m sorry that I…”, or “I feel bad about doing…”). Don’t spend time or energy making excuses or explaining your actions, keep it short.

- Resolve: Figure out how to fix it, or briefly describe your plan for not repeating the mistake in the future. This means really learning from the experience and changing your behavior in a helpful way.

Remember, there is no such thing as a perfect parent, and we will all continue to flip our lids and make mistakes from time to time. The process of repair gives you a chance to model cleaning up afterwards and fixing your mistakes, and is a powerful opportunity to teach these skills to your child.

A few days ago I was minding my own business, puttering around the house doing one thing or another, when I heard a loud noise that sounded like a cat hissing, growling, and crying at the same time.

It was the cat. Hissing, growling, and crying at the same time.

Our son has a love/torture relationship with our cat. He really does love her, and when I say “torture”, I really mean “have fun in ways that are not conducive to the animal’s short- or long-term physical and/or mental well-being.” I don’t think that he is being mean on purpose. But when I hear a noise like I heard, my instinctive and hard-wired reaction is to act as if he was. This equates to a loud, sharp admonition to leave the cat alone, NOW. And, often, a threat to find a new home for the cat if we can’t feel like she is safe with us. In my defense, I’m looking out for the cat’s safety, and I explain this to my son when I try to repair once he’s calmed down a bit. But the repair may not be necessary without my “acting as if”. As if he were taking pleasure from torturing the cat, and treated her purposefully in ways that cause her pain, fear, and discomfort.

It’s what organizational learning researcher Chris Argyris refers to as “espoused theory” vs. “theory in use”. My espoused theory, or belief that I will profess to anyone that asks, is that my son is a sensitive, loving boy, that truly cares about our cat and her well-being. But my theory in use, or driver of my default reaction, is that he causes her pain for his personal enjoyment.

But I can learn to pause between reflex and reaction. And due to the magic of neuroplasticity, I can begin to rewire my neural pathways.

This, to me, is the first step towards resolving the conflict between my espoused theory and my theory in use. It’s the first step in learning not to “act as if”.

Here’s the practice:

- Reflect after the fact on the way I reacted to a given situation.

- Maintain compassion for myself, and accept the fact that my reaction was instinctive and so beyond my conscious control.

- With awareness, the next time I find myself in a similar situation, try to recognize my instinctive reaction before I externalize it. In other words, pay attention to what I am about to do before I do it.

- Try to insert a pause between my instinctive reaction and my resulting action.

- Fail.

- Try again next time.

- Repeat as necessary until I am able to insert a pause, even if only for 1 or 2 seconds.

- Practice extending that pause.

- Practice consciously changing my action to be rational and considered, rather than reactive.

- Repeat – accepting that I will have occasional reversions to previous reactive behavior.

- Keep practicing.

- Decide that I want to change.

- Practice changing.

- Keep practicing.

It’s okay to let go of the expectation that you’ll ever be perfect, because you won’t. No one can be. Intentions matter. If you form the intention to pay attention to when you are “acting as if”, you have taken the first and most important step towards “acting as is”.

Try this – watch your child, for just a few seconds or minutes, without making judgments or drawing conclusions of any kind. Try not to identify behavior as good or bad, desirable or undesirable, acceptable or in need of correction. Try to simply observe them. And, if you like, see if you might be able to imagine what they are experiencing, in that moment.

At least several times a week I catch myself making snap value judgments about things I see my son doing (usually negative – watching TV is bad, torturing the cat is very bad), and I try to gently guide myself back to some level of nonjudgmental awareness, at least for a moment. To create that critical gap between observation and reaction, if only for a few seconds, that gives me a chance to see what he’s doing in a different light, from another perspective besides my instinctive reaction.

When I do, instead of seeing him about to break the chair, I might see him using his imagination and flying a spaceship. Instead of seeing him about to crush the cat, I see that he’s protecting her with his arms while he hugs her.

Of course, for every time I catch myself, there must be 5 more when I don’t. So I try to have a little nonjudgmental awareness of my own behavior too.

Mistaken Goals chart (Belief Behind the Behavior) [PDF file]

Mistaken Goals – chart of parenting interventions [PDF file]

All human beings want to belong. What we call misbehavior is typically the child’s misguided solution to problems they perceive related to belonging and connecting. Behind the behavior is often a mistaken belief about how to achieve belonging and significance. But this belief is hard to identify, and usually the child isn’t even consciously aware of it.

Enter the mistaken goals chart. This chart can be used as a Rosetta stone to decode the belief behind the behavior, and the key can be found in the feelings that the behavior generates in the adult. The connection may not be obvious, but with some experience using the chart, it begins to make more and more sense.

Start with your feelings in column 2. Are you feeling annoyed? Challenged? Hurt? Helpless?

Follow the appropriate row back to column 1, to confirm that the child’s behavior is aligned with the feeling you’ve identified. If it doesn’t match, reflect a little more on your feelings, as sometimes there are layers, and layers.

Once you feel confident that you’ve identified the right row, if you want to skip ahead to the payoff, look at column 7 for effective responses to the behavior. The other columns either help to confirm that you’ve identified the relevant belief, or offer preventive measures to avoid the behavior in the future.

Rudolf Dreikurs, who initially identified the four primary mistaken goals (Undue Attention, Misguided Power, Revenge, and Inadequacy) was famously asked, “Why do you keep putting children in these boxes?” His reply – “I don’t keep putting them there. I keep finding them there.”

Attached to the top of this post are PDF files of the Mistaken Goals chart and a list of parenting interventions to help address the beliefs behind the behavior – the cause of the behavior, rather than the behavior itself. Try them on for size! With practice, you may find them to be valuable tools.

More on Mistaken Goals and the Belief Behind the Behavior to come… let us know if it’s worked for you, or if you need any additional help navigating the charts, in the comments.

(Note that the attached chart was adapted by Jody McVittie from a similar schema created by Steven Maybell and Jane Nelson, and was based on the psychology of Alfred Adler and Rudolf Dreikurs.)

Update May 2024:

I’ve posted an update to the Mistaken Goals chart here – please click over to continue exploring!

Helping teens explore the consequences of their choices is much different from imposing consequences on them. Imposing a consequence (a poorly disguised punishment) is designed to make kids pay for what they did and usually invites rebellion. Curiosity questions invite kids to explore what happened, what caused it to happen, how they feel about it, and what they can learn from their experience.

— From Positive Discipline for Teenagers, by Jane Nelson, Ed.D., and Lynn Lott, M.A., M.F.T.

I wanted to share my thoughts about how a concept called double loop learning might be applied to a Positive Discipline practice.

This was triggered after attending an Agile software development presentation by Derek W. Wade called “Uncover Your Frames” that showed how to apply the theory to technical teams, but it was originally described by Chris Argyris, a prominent business theorist, in his work regarding organizational learning. A summary of several of Argyris’s contributions to the field of experiential learning, including single- and double-loop learning, can be found here: http://www.infed.org/thinkers/argyris.htm

The root of Argyris’s theory suggests that learning involves detecting errors in knowledge, and then correcting those errors. When applied to a person’s behavior, and the results of that behavior as observed by someone else, the single-loop learning model describes ‘making inferences about another person’s behaviour without checking whether they are valid and advocating one’s own views abstractly without explaining or illustrating one’s reasoning’ (Edmondson and Moingeon 1999:161).

In other words, we tend to draw conclusions about the reasons for another’s actions that are based in our mindset and past experience, and then act based on those unsupported conclusions.

As a parent, I find myself often using this model to explain my son’s behavior. For example, if my son is playing when I let him know that it’s time for dinner, and he doesn’t come to dinner, I assume that he heard my request and chose to ignore it, when in fact the request might not have even registered because he was so wrapped up in his play. Continuing to use single-loop learning, I might apply another assumption about the reasons for my son’s behavior based on past experience or my current mood or mindset, which leads to yet another unsupported conclusion, and an unsupported reaction.

So the single loop learning model can easily result in misunderstanding his reasons for his behavior, and consequently I am prone to making mistakes in my reactions to his behavior. This often leads to a defensive reaction on my son’s part, and eventually a power struggle or some other form of negative reaction that then becomes the focus for the situation.

In the double-loop learning model, rather than allowing assumptions to determine the observer’s reaction to the actor’s behavior, the observer takes one step further backward in the cause and effect chain to examine and challenge their own beliefs about the reason for the behavior, allowing an opportunity for the actor’s actual intentions to be considered, which might lead the observer to react differently based on new knowledge that is more aligned to the context of a particular situation.

Context is often hidden, but it always matters.

A child’s beliefs and goals lead to the child’s behavior, which leads to the effects of that behavior. But as parents, we often make unvalidated assumptions about the reasons for a child’s behavior, and react based on the behavior alone, without trying to “get into the child’s world” to understand what motivated them, which might lead us to a different reaction.

As described in Derek’s presentation (modified slightly here), the observer might instead use a framework such as:

“I noticed that (observable fact). I’m surprised because (reason for surprise). I’m curious about what you were thinking when (above observable fact). Could you share it with me?”

Double-loop learning is reflective, and can be initiated by the practice of stating observations without blame, shame, or pain, and asking curiosity questions, as encouraged by Jane Nelson and her co-authors in the Positive Discipline materials.

Using my earlier example, after observing my son’s behavior (continuing to play rather than come to dinner), rather than assume he had ignored me, I might connect with him, engage his attention, and say:

“I noticed that you are still playing. I’m surprised because I’ve asked you to come to dinner, and we’ve already talked about having dinner on time, so that we have time to play a game later. I’m curious about what you were thinking when you kept playing… could you share it with me?” I might then find out that he didn’t hear me when I asked because he was focused on what he was doing, and reflect that I hadn’t actually been certain of his attention at the time.

Which offers an excellent opportunity to avoid an unnecessary power struggle.

If for no other reason than that, we might consider trying to make a practice of double loop learning in our parenting. I can think of a few potential keys to success in this practice:

- Avoid preemptive judgements.

- Avoid assigning blame, shame, or pain.

- Approach the situation with genuine curiosity.

I’d invite you to try it, at least once. While reflecting on the results, try to have some curiosity about what might have influenced those results. Then, maybe, try it again.

That’s right… you’ll be applying double loop learning to the practice of double loop learning!

Here is a list of parenting resources that we’ve put together for a 7-week parenting workshop that we are currently facilitating.

Links to Positive Discipline books at the Seattle Public Library:

All books, including ebook versions

Positive Discipline

Positive Discipline A-Z: 1001 Solutions to Everyday Parenting Problems

Positive Discipline for Preschoolers

Positive Discipline: The First Three Years

Positive Discipline for Teenagers

Links to Positive Discipline books at Amazon:

Positive Discipline

Positive Discipline A-Z: 1001 Solutions to Everyday Parenting Problems

Positive Discipline for Preschoolers

Positive Discipline: The First Three Years

Positive Discipline for Teenagers

Positive Discipline Tool Cards and App:

Description and list of all versions

App Store (iPhone, iPad)

Google Play Store (Android)

Amazon Appstore (Android, Kindle Fire)

PD Websites and Blogs:

Positive Discipline Association free resources (handouts, articles, Q&A, videos, etc.)

Dr. Jane Nelson’s Positive Discipline blog

Resources for parents at Sound Discipline (Dr. Jody McVittie’s organization)

Positive Discipline forums/discussion groups on Ning, a ridicuously supportive online community of teachers, parents, and parenting educators (join and you might get a personal welcome from Jane Nelson!) (UPDATE: This forum appears to no longer be functioning, looking for a replacement to add here instead.)

Parenting classes and workshops:

Positive Discipline online parenting class – facilitated by Dr. Jane Nelson, “The six-session online course includes Positive Discipline video lessons that will teach you the most important, family-changing skills from the Positive Discipline books and live classes. The class includes a colorfully illustrated e-workbook with experiential activities, e-cards with parenting tips, and e-book version of the Positive Discipline book.”

Live parenting classes and workshops from the Positive Discipline Association – both in person and remote options are listed.